Pushing the F-22 to its limits as a test pilot was fun enough to bring “a little-kid grin” to Col. Jack Fischer’s face.

But blasting into outer space in a Soyuz spacecraft in April was like nothing he had ever experienced before.

“The Raptor’s got a good kick in the pants, but it doesn’t have a million horsepower,” Fischer said in a Nov. 6 interview at the Pentagon. “It was a heck of a kick in the pants, and the thing is, the kick just kept on coming.”

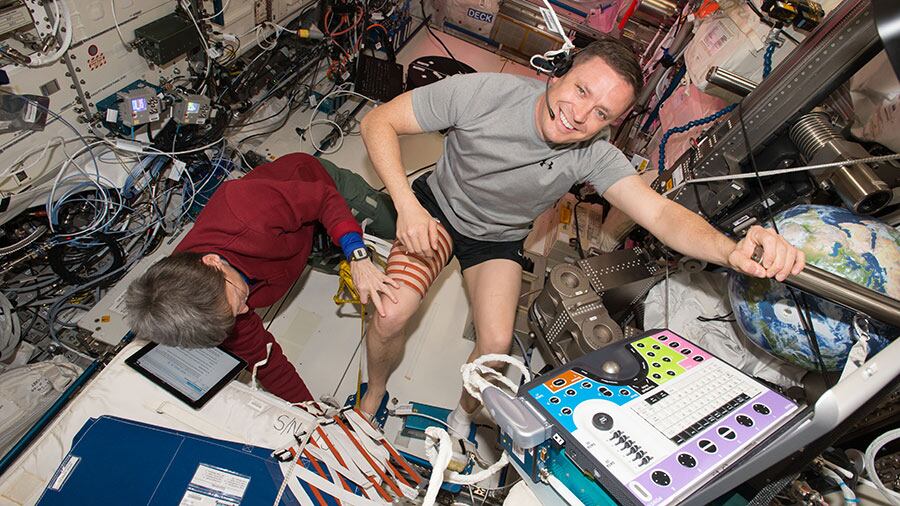

Fischer, an Air Force pilot and Air Force Academy graduate, spent about five months aboard the International Space Station as a flight engineer during his first trip to outer space, before returning in early September. During that time, he conducted two spacewalks and worked on about 300 experiments with his companions, space station Commander Peggy Whitson, who broke the American record for most cumulative days in space shortly after Fischer arrived, and Russian cosmonaut Fyodor Yurchikhin.

The entire experience was awe-inspiring from the start, he said.

For 8 1/2 minutes, Fischer experienced “the best acceleration of any plane I’ve ever had.” Then, all of a sudden, he was weightless, and he looked out the window and saw the entirety of the planet Earth for the first time.

Glimpsing the curvature of the Earth at 60,000 feet in a Raptor was “nothing compared to being a couple hundred miles up, and you see this thin blue line that all life that we know of on Earth exists within,” he said.

Fischer said he was so enraptured that Yurchikhin, who also took off in that Soyuz, had to nudge him to bring his attention back to the mission. The time for introspection was over ― he snapped back and focused on the job he had to do.

RELATED

Later, during his months in orbit, he had plenty of time to gaze at the stars “and contemplate life and my place in the universe.” Yurchikhin, an experienced cosmonaut on his fifth trip to space, gave Fischer plenty of pointers on how to take the best pictures of Earth.

Fischer’s pre-launch expectations for living in space were already high, but even he didn’t imagine how much fun he would have there.

“You’re floating all the time, you’re playing with your food, you’re looking out the window at these amazing views,” Fischer said. “It was shocking. You see it on television and you’re kind of like, ‘That looks pretty cool.’ I’m not a small guy, so I felt like a space ballerina. I felt like I was very flexible and graceful, and the truth is, I’m really not. But I felt like it up there.”

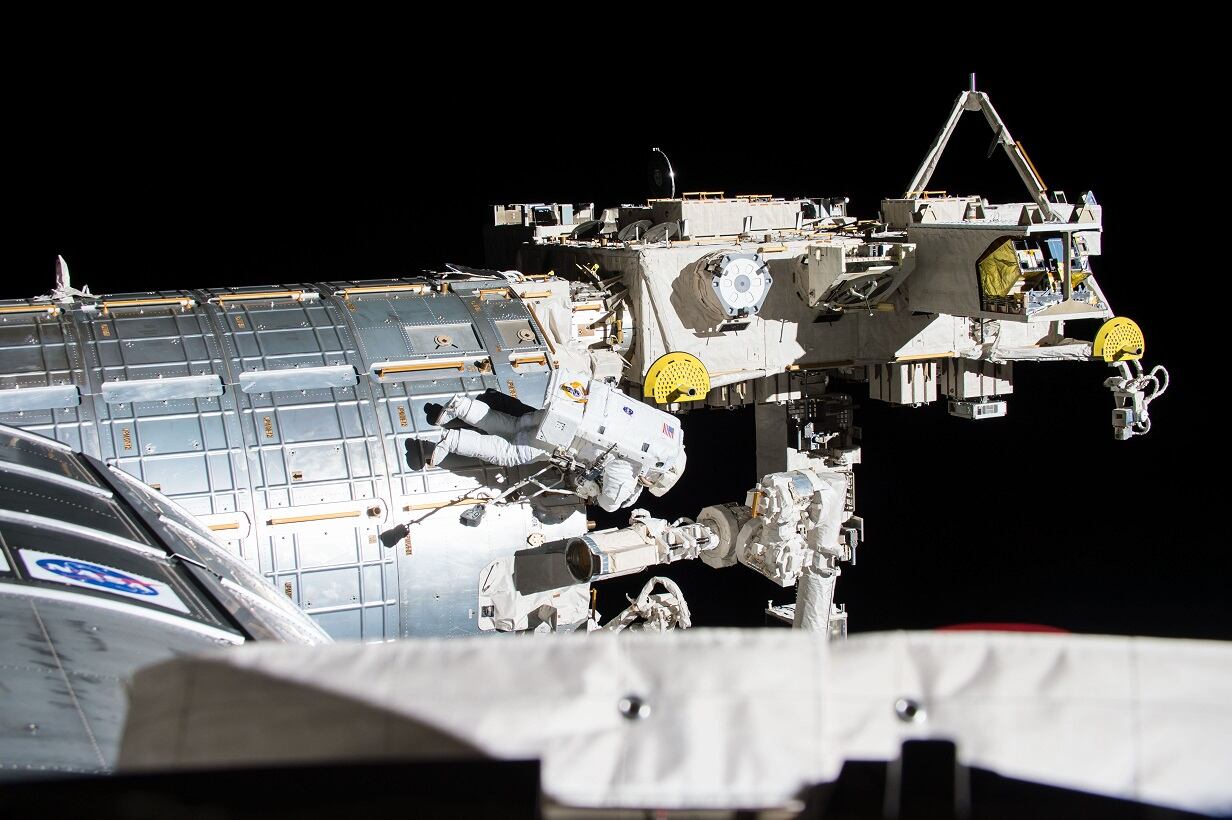

As cool as that was, his spacewalks were even better.

“There was nothing in between you and space except a little visor,” Fischer said.

Stepping out into space for the first time on May 12 felt kind of like skydiving, he said.

“That first step is a doozy,” Fischer said. “When we come out the hatch, we’re usually feet down, and the Earth is right there underneath you going by at 17,500 miles an hour. You appreciate that moment, then you click it off and compartmentalize and go to work.”

The first time, Fischer and Whitson repaired systems like a Japanese robotic arm and putting shields on a docking port for new commercial crew vehicles, which could eventually allow private spaceflights to bring people to the space station. It was the 200th spacewalk at the station.

A few weeks later, he had to conduct an emergency spacewalk to fix a failed computer that controlled several external systems. If they didn’t fix it, he said, “we’d be in a world of hurt.”

Whitson broke the American record for most cumulative days in space on April 24. Fischer said they celebrated by hanging a banner he had made that said “Congratulations Space Ninja” ― his nickname for the veteran astronaut. Whitson ― who Fischer described as a “humble legend” ― rolled her eyes and groaned at the hoopla.

They also received a phone call from President Trump celebrating the occasion. During the call, they discussed the importance of science, technology, engineering and mathematics education with the schoolchildren who were also on the call.

The space station crew conducted experiments on things like new technologies for exploration, ways to create lighter and stronger alloys, and new medicines to treat diseases like cancer.

The microgravity cancer research was particularly important to Fischer, since his daughter beat cancer two years ago. He called the drug ― azanofide antibody-drug conjugates, or ADC ― “a cancer-seeking missile” that hunts down and eliminates cancer cells in lung tissue and eases the side effects of chemotherapy.

“The ramifications of that for everybody are pretty mind-blowing,” Fischer said. The space station is “just such a great national laboratory. I’m excited about how much science we get through every day now, and the tidal wave of things we’re going to discover with the space station up there.”

The astronauts also experimented with drugs that spur bones to grow. That’s important for astronauts, who could lose up to 20 percent of their bone and muscle while in space if they don’t take preventative measures. But it could be even more important for troops wounded on the battlefield and other trauma patients as they recover, he said.

Fischer hasn’t been back on Earth long, but he’s eager to return to space ― perhaps on the new Orion spacecraft NASA is developing. He’s excited about the rise of commercial space travel and space tourism. And if there’s ever a mission to Mars, he would go ― but only if his wife could come too.

“Exploration’s important,” Fischer said. “It’s worth the risk, it’s worth the sacrifice for us to grow as a species and get better. Space is the key to our evolution, and I think we need to continue to explore to do that.”

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.