It was a hot day at Washington’s National Airport on July 26, 1947, as President Harry S. Truman’s limousine drove up to the aircraft popularly known as “Sacred Cow,” a Douglas C-54 Skymaster. Truman was on his way to visit his mother, who was gravely ill with pneumonia. But before the president left, he intended to sign an important piece of legislation — the National Security Act of 1947, an executive order passed by Congress the previous day defining the roles and missions of the armed forces — as well as his nomination for the first secretary of defense. In the end, Truman had to wait nearly an hour in the sweltering heat for the historic documents to arrive.

It took only a few minutes for the president to sign the paperwork, but it had taken decades to bring about these fundamental changes in the United States military organization. The Security Act’s primary purpose was to merge the Department of War and the Department of the Navy into the National Military Establishment, to be headed by a secretary of defense. Further, it authorized the establishment of the Air Force as an independent service, marking the culmination of a national debate that had begun four decades earlier.

RELATED

Soon after the Wright brothers proved their theories of powered flight, author H.G. Wells, in his 1908 book “The War in the Air,” foresaw that the air power of nations would revolutionize the conduct and social consequences of war. In 1909, Italian Army Major Giulio Douhet saw the potential of fixed-wing aircraft and predicted that the sky “is about to become another battlefield no less important than the battlefields on land and sea.” He also foresaw the consequences of allowing air power to be restrained by ground commanders and advocated the creation of a separate air arm led by airmen.

The rapid improvements in winged aircraft also prompted several American lawmakers to think ahead and propose that air forces should be organized so they could act independently. In February 1913, Rep. James Hay of Virginia proposed a bill that would have created a separate aviation corps as one of the line components of the Army. Rep. Charles Lieb of Indiana introduced a bill in March 1916 to create an independent air force. Neither bill went beyond committee hearings.

Battles of opposing forces in the air became a fact during World War I in Europe. Winston Churchill, then minister of munitions for the British war effort, regretted in October 1917 that there had been no study of the possibilities of organizing air operations “not merely as an ancillary service to the special operations of the Army or Navy, but also as an independent arm cooperating in the general plan.” Britain, in fact, established the world’s first independent air arm on April 1, 1918, when it merged the army’s Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service into the Royal Air Force.

In May 1919, U.S. Assistant Secretary of War Benedict Crowell headed a commission to study the military aviation arms of allied countries during the recently ended conflict. The commission’s report recommended a unified air organization co-equal to the Navy and War departments, to include military and civilian aviation. A flurry of bills was subsequently initiated, and the first hearings were held in 1919 by Rep. Fiorello LaGuardia’s House Committee on Military Affairs aviation subcommittee.

LaGuardia, who had served as commander of an air unit on the Italian front, was aviation’s leading voice in Congress. He backed efforts to detach the Army Air Service from the grip of the Army’s ground-bound general staff and supported a bill, introduced by Rep. Charles Curry, calling for a regular Air Force, Reserve and National Guard. At the same time, Sen. Harry New introduced a bill for a U.S. Air Force in a Department of Aeronautics that would control the military but also aviation in other government departments as well as commercial air operations. None of those legislative efforts received any worthy support.

In 1923 Maj. Gen. Mason Patrick, chief of the Air Service, appointed a group of officers led by Brig. Gen. William Lassiter “to consider in all details a plan of war organization for the Air Service” and told the secretary of war that “our Air Service [must] have a strength and an organization permitting rapid expansion to meet the requirements of a war and then be capable of steady expansion to meet the ultimate requirements of the war.”

Lassiter’s report cautioned that “unless steps are taken to improve conditions in the Air Service it will, in effect, be practically demobilized at an early date.” A 10-year program was recommended, to include a force of bombardment and pursuit units to carry out independent missions under the command of the Army general staff. Such an expansion would cost an estimated $495 million.

The Lassiter report was forwarded to Secretary of War John Weeks, but its recommendations never got airborne. President Warren G. Harding’s death in August 1923 brought Vice President Calvin Coolidge into the White House. Coolidge was committed to a rigid economic program that did not include funding for aviation advances. His lack of interest in military flying prompted an undocumented story that he had asked Secretary Weeks: “What’s all this talk about lots of airplanes? Why not buy one airplane and let the Army pilots take turns flying it?”

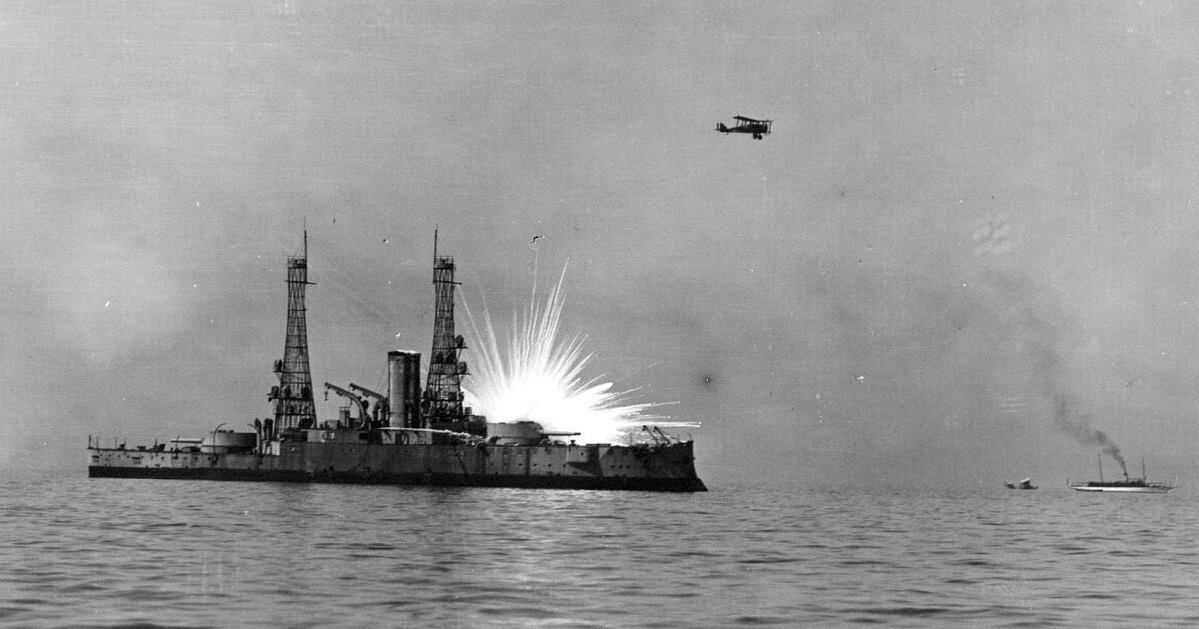

Into the political conflict after World War I stepped the fiery, outspoken Brig. Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell. Already known for his vitriolic criticisms of superiors and others in high places, he began a speaking and writing campaign calculated to alert the public to the sorry state of military aviation. He appeared before several congressional committees, but unfortunately for the air force’s immediate future, Mitchell’s credibility was crippled due to allegations that he did not back up his claims with sufficient proof. He was informed by Secretary Weeks that his actions rendered him “unfit for a high administrative post.”

Mitchell was court-martialed in November 1925 for insubordination and defiance of civilian authority and sentenced to five years' suspension at half pay. He elected to resign in February 1926.

Many Army Air Service pilots agreed with Mitchell about the sad state of military aviation, but they found themselves unable to condone his methods or publicly support his charge about “the incompetency, criminal negligence, and almost treasonable administration of the National Defense by the Navy and Army.”

At the height of the Mitchell tumult, in September and October 1925 President Coolidge called for a board of military men and civilians, chaired by Dwight W. Morrow, to study “the best means of developing and applying aircraft in national defense.” This board’s conclusion was a disappointment to those who wanted a separate air force. It found that the United States was in no danger of air attack and saw no reason for a separate Department for Air to coordinate with the Army and Navy departments, nor did it recommend the creation of a Department of National Defense. However, the board did recommend that the Air Service be renamed the Air Corps, with aviation representation on the Army general staff. Those provisions were included in the Air Corps Act on July 2, 1926, “thereby strengthening the conception of military aviation as an offensive, striking arm rather than an auxiliary service.”

The legislation also authorized a five-year program for the Army and Navy and development of a continuing research and procurement program with a goal of 1,800 planes, 1,650 officers and 15,000 enlisted men. But those goals were not realized because sufficient funds were never appropriated. The following years saw the beginning of the Great Depression.

No significant progress was made to improve the United States' military aviation program until January 1933, when the General Headquarters Air Force (Provisional) was established to test the feasibility of a central striking force under the top command of the Army.

Such a force was intended to defend the coasts and overseas possessions, leaving the Navy’s fleet assured of freedom of action with no responsibility for coastal defense. It followed then that the Air Corps could not defend American coasts and overseas possessions without bombardment and observation aircraft. This agreement gave the Air Corps the right to engage in seaward reconnaissance, which required the development of long-range bombers. But the Army general staff did not agree that the Air Corps should operate without Army support or be concentrated under a single air command. In October 1933, the War Department established a board, headed by Deputy Chief of Staff Maj. Gen. Hugh Drum, to study Air Corps policies. His board opposed any departure from previous War Department guidelines.

Meanwhile, Billy Mitchell continued to assert that American air power was inadequate, obsolescent and ranked last among world powers. During three months in early 1934, Air Corps pilots flew and died while taking over the task of carrying the U.S. Mail. As a peacetime test, however, the airmail operation proved valuable since it forcefully pointed out the serious inadequacies in Air Corps equipment and training.

The battle for a separate air force was still raging when Newton Baker, former World War I secretary of war, was tagged in 1934 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt with heading a new committee of inquiry, the 15th such group convened to study military aviation and the question of an independent air arm. The committee’s final report reflected the thinking of those whose minds were still closed to the airplane’s potential. The loudest voice on the committee against the creation of an independent air force was Gen. Drum, who believed the Air Corps should procure aircraft suitable for close air support of advancing troops.

Nevertheless, the concept of the General Headquarters Air Force had been approved, representing the first real step toward an independent air arm. It was created to provide a strategic striking force wherein all combat air units were under the control of the various Army corps commanders and organized administratively into four geographic air forces within the United States. It further provided for 980 aircraft, of which only 174 were short-range, tactical first line combat aircraft inadequate for long-range, strategic missions. Although these air forces were responsible for training, aircraft development, doctrine and supply, the Army ground force commanders still controlled the air bases, including the support personnel.

But one man on the Baker committee submitted a minority statement. Racing pilot James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle, then an Air Corps reservist, declined to sign the majority report because of the board’s refusal to support an independent air arm.

“I believe that the future security of our nation is dependent upon an adequate air force,” wrote Doolittle, who would go on to lead Doolittle’s Raiders in bombing runs against Tokyo and other targets in Japan in 1942 and become one of the heroes of World War II.

“This is true at the present time and will become increasingly important as the science of aviation advances and the airplane lends itself more and more to the art of warfare," he wrote. "I am convinced that the required air force can be more rapidly organized, equipped and trained if it is completely separated from the Army and developed as a separate arm. If complete separation is not the desire of the committee, I recommend an air force as a part of the Army but with a separate budget, a separate promotion list, and removed from the control of the General Staff.”

Later asked by a reporter what he thought about the report, Doolittle replied: “The country will some day pay for the stupidities of those who were in the majority on this commission. They know as much about the future of aviation as they do about the sign writing of the Aztecs.”

Brig, Gen, Frank Andrews was appointed the first GHQ commander in March 1935. He chose staff members who believed in developing bomber capabilities, and they prepared a doctrine that stressed precision bombing of enemy industrial targets by heavily armed long-range aircraft. Meanwhile, a small group of engineering officers at Wright Field, Ohio, had already been analyzing plans for low-wing, all-metal, multi-engine bombers.

In May 1934, the Army chief of staff authorized the negotiation of contracts for preliminary designs. The objective was to develop a 10-year plan to produce four different bombers, each to be progressively larger, faster and able to carry bigger bombloads over great distances. The Boeing B-9, Martin B-10 and B-12 were developed along those lines, followed by the Boeing B-17.

But there were still organizational problems. Andrews wrote an audacious letter to the House Military Affairs Committee endorsing an Air Corps Reorganization bill that would provide for the Air Corps to operate on an equal status with the ground Army and have its own promotion list and budget. The Army’s general staff members were appalled at that recommendation; in 1939 Andrews was reduced in rank from major general to colonel and transferred to San Antonio. His chief staff officers, all of whom later became generals, were also transferred to other locations. As one writer commented, “thanks to this bitter-end opposition, we came up to the brink of war with nineteen underdeveloped Flying Fortresses, a few trained crews, a starved organization for Air Power, and no law defining where Navy responsibility began and Army responsibility left off.”

The basic problem was still there: no unity of command and the GHQ Air Force was separated from the Air Corps, its logistic organization. But this dilemma was partially solved on June 21, 1941, when the War Department created the Army Air Forces and the GHQ Air Force became the Air Forces Combat Command. An Air Staff was authorized to plan and carry out the expansion of the entire air arm, with Lt. Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold named chief of the Army Air Forces. He was thus a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, serving under Army Gen. George C. Marshall as the Allies fought and won World War II.

Postwar planning had already begun when the nation’s military forces rapidly disbanded after the Japanese surrender in 1945. Arnold and his Pentagon staff lobbied for congressional legislation establishing a Department of National Defense with a separate Air Force on an equal basis with the Army and Navy. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower was for it, since he had seen that the Army and Air Forces could work together, provided there was a single decision-maker in charge. The Navy balked.

Doolittle explained his own view in his memoirs.

“If a Department of National Defense were not approved, we thought we might still get a separate and equal Air Force, wrote Doolittle, by then a retired general. "The advantage would be that the Air Force would be on a par with the other two services, both operationally and politically. However, the disadvantage would be that there would be three instead of two bickerers if there were not a single head of the whole establishment to knock heads together. Teamwork had won the war, not one single service.”

While the United States went through the throes of returning to economic normality, Congress vigorously debated the issue. The Navy’s worst fears centered on the powers of a secretary of defense and concerns that the Navy and Marine Corps aviation units would be given to the Air Force. Several unification bills were presented, and a compromise was finally reached that resulted in the National Defense Act of 1947, which created the National Military Establishment, including the office of the secretary of defense and the Departments of the Army, Navy and Air Force.

The missions of the Navy and Marine air arms and the Air Force were spelled out by Executive Order No. 9877. President Truman nominated James V. Forrestal, then secretary of the Navy, to be the first secretary of defense. Those were the documents that Truman waited to sign planeside on July 26, 1947, at National Airport.

The official birthday of the U.S. Air Force is recognized as September 18, 1947, the date when W. Stuart Symington, former senator from Missouri, was sworn in as the first secretary of the Air Force. Although Billy Mitchell did not live to see that day, his dreams about an independent air arm equal to the Army and Navy had finally been realized.

Originally published in the September 2007 issue of Aviation History, a sister publication.