NATIONAL HARBOR, Md. — Anduril is weeks away from flying its proposed U.S. Air Force collaborative combat aircraft for the first time, and the company said it is working to ensure its drone wingman will be semiautonomous from takeoff.

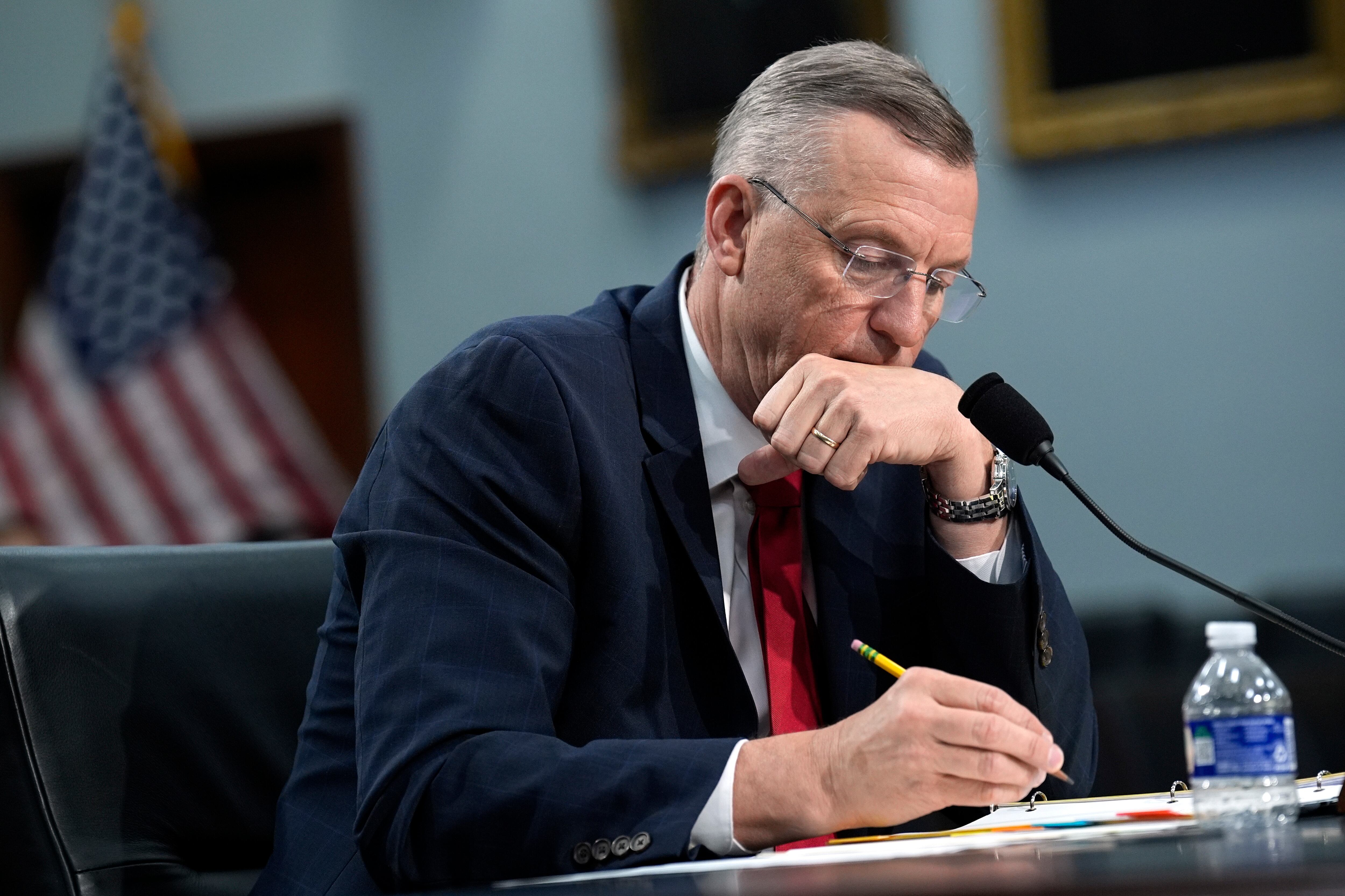

Air Force Secretary Troy Meink said Monday that Anduril’s collaborative combat aircraft, or CCA, will take its first flight in mid-October. Meink made his comments in a roundtable with reporters at the Air & Space Forces Association’s Air Space Cyber conference in National Harbor, Maryland.

Anduril’s drone, designated the YFQ-44A, is one of two that the Air Force is considering for its first increment of the CCA program, along with General Atomics’ YFQ-42A. General Atomics’ CCA took flight for the first time in August at an unidentified location in California.

In a briefing with reporters Monday, Anduril officials said they were “within spitting distance” of the YFQ-44A’s first flight, and expressed confidence in their ability to adhere to the program’s schedule.

Developing a fleet of semiautonomous CCAs to fly alongside advanced crewed fighters like the F-35 and F-47 is a top priority for the Air Force. The service wants a fleet of at least 1,000 CCAs to conduct strike missions, collect reconnaissance, carry out jamming operations and even serve as decoys to lure enemy fire away from the fighters.

The Air Force announced in April 2024 that Anduril and General Atomics had won the first CCA contracts, and the service plans to develop additional CCA versions in an incremental approach.

In a graphic posted online in May, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David Allvin said CCAs would have stealth comparable to that of the F-35, a combat radius of more than 700 nautical miles — greater than the F-35A and F-22 — and be operational later this decade.

Anduril is now in the final stages before beginning the YFQ-44A’s flight testing, with multiple vehicles undergoing ground testing at the company’s test facility, said Diem Salmon, the company’s vice president for air dominance and strike.

Having several copies of its CCA available will make it easier to launch a “more expansive flight test profile” in 2026, Salmon said.

Anduril deferred to the Air Force when asked about Meink’s prediction of a mid-October first flight.

From the start, Salmon said, Anduril’s goal has been to ensure its CCA is semiautonomous in all aspects, from takeoff to flight to landing. The YFQ-44A has already been conducting semiautonomous taxiing, she said, which means “we hit a button, it goes to the points that’s been designated by that vehicle, completes its taxi [and] returns.”

Similarly, she said, Anduril wants the YFQ-44A’s first flight to involve takeoff and landing at the push of a button.

“There is no stick and throttle,” Salmon said. “It will be able to execute the actual first flight profile, preplanned, using autonomy software on the vehicle.”

While the YFQ-44A’s first flight will not be remotely piloted by humans, Salmon said, there will still be humans on the ground overseeing what the CCA does.

General Atomics spokesman C. Mark Brinkley said it conducts first flights of all new aircraft, including the YFQ-42A, with remotely piloted flights to better collect data and minimize risk.

“The performance data obtained this way is invaluable to the success of our aircraft programs,” Brinkley said. “We have no reason to and no interest in doing it any other way.”

Brinkley said General Atomics’ autonomy track record is proven, and drones such as the Gray Eagle, Reaper, Avenger and others regularly use the company’s automatic takeoff and landing capability.

“YFQ-42A is designed for semiautonomous flight, and that’s not even in question,” Brinkley said. “This is like saying I never expected my baby to crawl, but go straight from the crib to the Air Force Marathon.”

Salmon said Anduril’s decision to jump straight to semiautonomous flight with the YFQ-44A meant its engineers had to work hard to get the software right, and that has taken more time.

“The team has been heads down, getting to that goal for CCA,” Salmon said. “There’s just a little bit more on the software development side that needs to get wrung out. That’s what’s currently driving our schedule right now.”

But achieving semiautonomous flight early, even if it means a later first flight, will allow Anduril to progress through testing more quickly, she said.

“That’s going to allow us to leapfrog the overall test plan, because we are tackling that hard part first,” Salmon said.

Jason Levin, Anduril’s senior vice president of engineering for air dominance and strike, also said the company did not have its own ground control station for a human to handle takeoff and landing, and would have had to develop one if it didn’t go straight to semiautonomous flight. That would have been “a step backwards, because we really want to get to this semiautonomous thing and wring out that problem.”

Levin said development of the company’s CCA has moved quickly, from passing its preliminary design review in 2024 to launching ground testing in May. That is the same month General Atomics’ CCA began ground testing.

The software required to semiautonomously fly the YFQ-44A required a major in-house development effort and a “clean sheet” design, Levin said. The company has developed similar software for other products, he said.

“But to get to the level of rigor and complexity for CCA has been a different beast to handle,” Levin said. “It’s been a parallel effort, [with] the hardware teams working everything from electrical systems, avionics, fuel system and the jet itself, as well as the software” at the same time.

Levin said Anduril’s CCA will first fly with only its semiautonomous flight capabilities intact, and the programming to carry out missions will come later.

Integrating the software with the YFQ-44A’s avionics and other hardware has been the greatest challenge so far, Levin said.

Anduril’s timeline for first flight is a slight slip from its predictions earlier this year. After Anduril’s CCA entered ground testing in May, the company said it expected to begin flight tests this summer.

Anduril officials downplayed the significance of conducting their first flight in the fall instead of the summer.

“It was not a race to get to first flight as fast as humanly possible,” Salmon said. “It was, how do we field this really advanced and novel capability as fast as we can? And with that comes the recognition that the autonomy is the hard part here.”

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.