Elegance Bratton is sitting on a park bench in Washington Square Park. Just to the east is the New York University building where he studied film. A little to the west is the Christopher Street Pier where Bratton, at 16, found a home among other homeless, gay youths after his mother kicked him out of their New Jersey apartment for being gay. The first time he held hands with a boy was here.

“I’ve been homeless on these streets. I’ve been starving on these streets. I’ve not had train fare to get back home on these streets,” Bratton says. “To walk here now, there’s a lot of triumph. This little path from here to the pier was where I cut my teeth.”

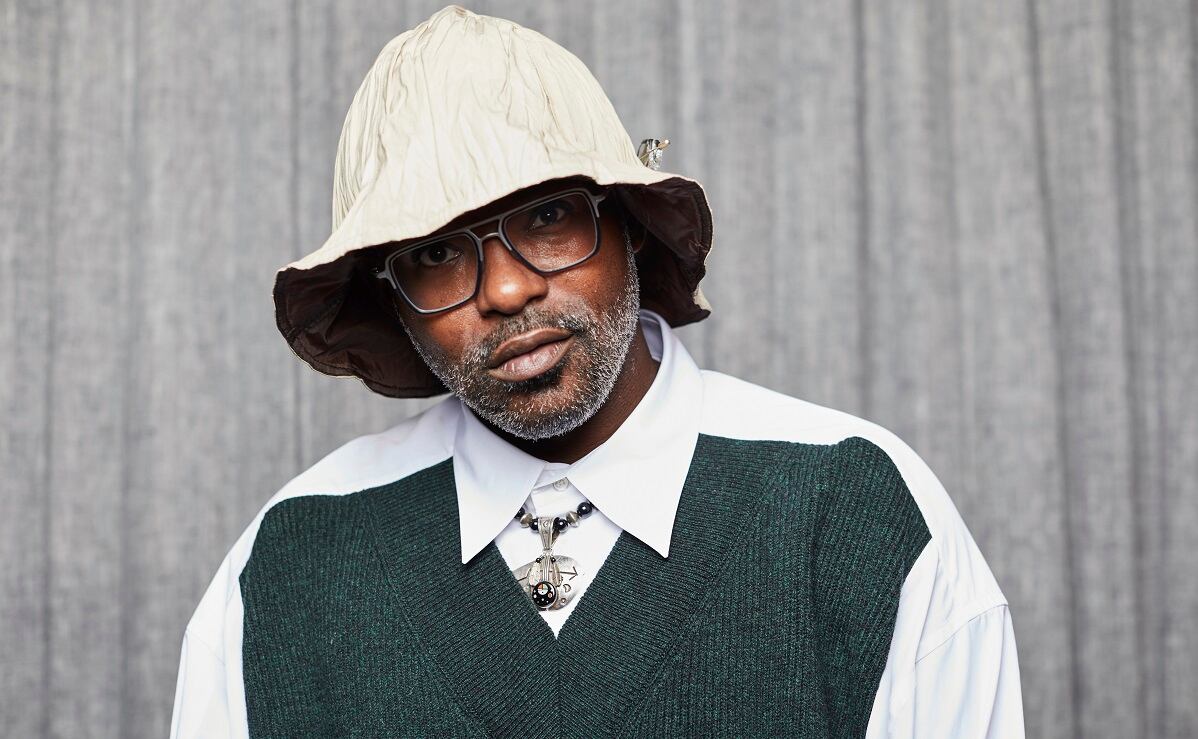

The path that Bratton, 43, has taken to this moment is by any measure remarkable. Within days of meeting a reporter on a recent bright fall day, Bratton’s “The Inspection,” an autobiographical drama about his experience in boot camp as a Marine, made its red-carpet premiere uptown, at Lincoln Center, at a New York Film Festival gala.

Such heights might have once been unthinkable for Bratton, who spent a decade homeless before enlisting with the Marines as a way to win back his mother’s affection. But for Bratton, who grew up rehearsing his moment in the spotlight and practicing his red-carpet walk, it’s more like realizing a very hard-earned destiny.

RELATED

“What we’re doing right now, I’ve done in the shower by myself probably since I was 7 years old,” Bratton says, chuckling. “It’s like being reborn into one’s dreams. When I was homeless, almost in this very spot some 20 years ago, I remember saying a prayer that I could thrive. I had no idea that at that moment, God had already said yes.”

“The Inspection,” which A24 released in select theaters Friday and expands in the coming weeks, is Bratton’s first feature film and one of the standout debuts of the year. It’s the clarion sound of a new voice in film that reverberates all the more powerfully for coming from a man who spent the first half of his life being told again and again that his life, as a queer and poor Black kid, was worthless. “Every frame,” The New Yorker wrote, “thrums with passion and purpose.”

Jeremy Pope plays a fictionalized stand-in for Bratton: Ellis, a 25-year-old living in a homeless shelter after he’s been all but abandoned by his mother (Gabrielle Union). He joins the Marines during the “Don’t ask, don’t tell” period of U.S. military service. There he encounters abusive hazing that nearly kills him but also a soldierly camaraderie that transcends social divisions. Some of the torturous drill sergeant-scenes in the barracks will remind many of Stanley Kubrick’s “Full Metal Jacket,” but “The Inspection” has more complicated things to say about the nature of identity, transformation and community.

“Isn’t every family abusive?” says Bratton, sitting alongside Chester Algernal Gordon, his producing and life partner. “To me, family is where you find it. I found family on the piers of Christopher Street. I found family in the halls of Columbia University. And I found family at boot camp. Love sometimes isn’t because of. It’s in spite of.”

Bratton, himself, was contemplating his future after 10 years of living in and out of New York shelters when his mother told him to enlist. All around him, Bratton saw increasingly grim odds for himself. Shelters, he noted, were full of Black men not unlike himself, stuck in a cycle of survival.

“I had to ask myself if that was my future,” says Bratton. “The next morning, a Marine Corps recruiter approached me and said, ‘Do you want to be a Marine?’ I said, ‘If I can look as good in that uniform as you do, please sign me up.’”

After scoring well on the entrance exam, Bratton was offered several options. One was to learn filmmaking and make instructional videos for the Marines. That appealed to Bratton, whose homeless hustles included stealing art books. Everyone in stores assumed he wasn’t interested in them. That’s how Bratton encountered books by Martin Scorsese and Spike Lee, and Peter Biskind’s 1970s Hollywood history “Easy Riders Raging Bulls.”

“So when the recruiter asked, ‘Have you ever thought about being a filmmaker?’ I was like, ‘Of course. Doesn’t everybody?’” recalls Bratton.

In the Marines, Bratton endured hostility but also found the most pivotal experience of his life. In some ways, the military was more accepting of him than his own family had been. “The Inspection,” to Bratton, is about “radical and defiant empathy” amidst political division.

“Yeah, it was abusive to me but it was also the place I found my purpose,” he says. “Just like my mom, it rejected me and embraced me. And in the process, I got to know myself.”

After completing boot camp, Bratton found he could apply the tools he learned as a Marine in more personal ways. His mother told him to bring his camera and shoot his sister’s graduation. There, he found none of her classmates or instructors had heard of her older brother.

“It incensed me,” says Bratton. “I resolved in that moment that I would become a filmmaker so that I couldn’t be erased by my family. They were going to go to a theater and see my name on a poster, they were going to turn on the TV and see my name in the credits.”

After the Marines, Bratton found new entries to higher education. He attended Columbia University. A sociology class led him to begin making what would become his breakthrough documentary, “Pier Kids,” an intimate, immersive portrait of the Black LGBTQ community on Christopher Street Pier, made by an insider. He began it with money raised on Kickstarter and using his Marines’ camera.

“They call it ‘getting caught up’ on the pier. You get your first gay kiss or trans kiss, you smoke your first blunt. Ten years later you’re 30. You get caught up in because it’s intoxicating to find your tribe,” says Bratton, who now lives in Baltimore, Maryland, with Gordon, their dogs named Lindsey Lohan and Caravaggio, and a stray cat that followed him home one night. “I still go back to the pier whenever I come to New York City.”

After Bratton made the 2018 Viceland 10-episode docuseries “My House,” about New York’s ball culture, he found himself with money and opportunity for the first time. He considered writing a book about his life. Gordon urged him to write a screenplay, instead. While developing “The Inspection” at the NYU Production Lab, filmmakers like Spike Lee, Kasi Lemmons and Tony Gilroy gave him advice. Lee suggested he not lay the film out in flashbacks. After pitching it around Hollywood, A24 greenlit it. Just days later, Gordon received an even more dramatic phone call.

“I came out of the bathroom and Elegance was standing there crying,” Gordon says. “And he doesn’t really cry, except for this one movie. He said, ‘My mother was just killed.’”

The death of Bratton’s mother has cast a tragic shadow over “The Inspection.” The film is dedicated to her. For that reason and others, Bratton has found he can’t watch his movie before speaking at a post-movie Q&A. It’s too emotionally overwhelming.

But if “The Inspection” is a product of the pain of Bratton’s past, it’s also a stirring portrait of his strength and resiliency. Bratton, emboldened by the response, is ready to make 30 more films, he says. “It’s like he’s walking in destiny now,” says Gordon.

“I wanted this story for a generation that I know is going to have to fight through hell to be themselves,” says Bratton. “But I wanted to make a movie that they would feel confident that they can get to the other side and persevere. The movie is proof that they can.”

___

Follow AP Film Writer Jake Coyle on Twitter at: http://twitter.com/jakecoyleAP