The Air Force is getting serious about great power competition, and the focus isn’t solely on the actions of generals in smokey war rooms. Ordinary airmen, those who defend a base, arm aircraft and build infrastructure, will be required to stand post in a future conflict involving peer-level adversaries like Russia.

Airmen can no longer depend on the long-standing, well-developed facilities like those through which they’ve rotated in the Middle East for going on two decades.

This month, airmen from Ramstein Air Base in Germany headed to northeastern France for a week-long exercise involving forward operating base construction and airfield operations in contested airspace, according to a U.S. Air Forces in Europe news release.

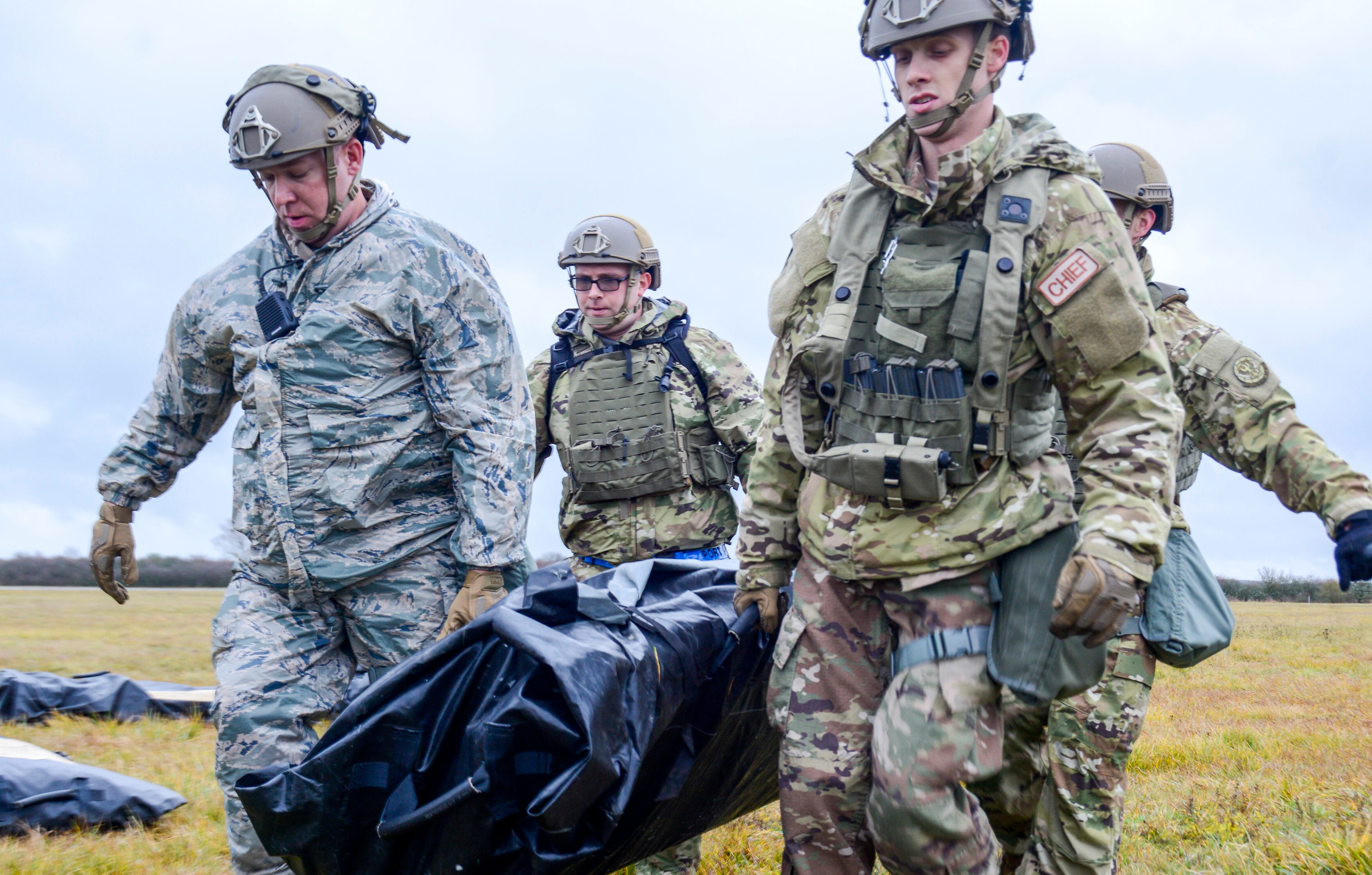

Airmen from the 435th Contingency Response Group and more than 11 other organizations, along with one C-130J Super Hercules aircraft assigned to the 37th Airlift Squadron, 86th Airlift Wing, deployed to Grostenquin air base to participate in the exercise known as Contested Forge.

“Our mission is to enable access and airpower across the continent of Europe,” said Capt. Michael Hester, a contingency response element operations officer with the 435th CRG. “We go into locations that can’t necessarily handle airfield operations, establish security, and build up so that we can start getting aircraft in the area and cargo into the airfield to enable access for airpower across the continent.”

During the exercise, airmen built and secured the base and conducted airlift operations, including container deliveries and heavy equipment drops, engine-running on-loads and combat off-loads, during the day and night.

And, of course, a simulated contested airspace would be nothing without simulated enemy fire.

The airmen brought along a man-portable aircraft survivability trainer and a smoky surface-to-air missile to simulate enemy fire on the aircraft during the exercise.

U.S. airlift and fighter aircraft alike are plenty used to dropping munitions and cargo in combat, but the threat level in Afghanistan and Iraq has been relatively low for a long time.

The Russian military is aware of U.S. airpower, as well as its limitations. The Kremlin has invested heavily in air defense and cyber warfare systems to knock out satellite advantages and limit the close-air support and air drop options the U.S. Air Force has during a conflict.

Additionally, a conflict with Russia would likely require air bases to be self-sustaining and self-defending for a significant, and potentially deadly, length of time.

Airmen will need to be prepared to hold off enemy assaults and act as isolated enclaves in the event that they’re cut off.

“Our capabilities include anything you would need to rapidly open an air base, and for a significant duration before support is needed to resupply,” said Maj. C.J. Thomsen, director of operations for the 435th CRG. “We do a lot of work with outside agencies to get things we need, such as fuel and water, but otherwise we are self-sustained.”

“Anywhere in the world we can find ourselves where we don’t have a runway, where we don’t have the means to catch an aircraft or refuel and resupply them,” Thomsen said. “By being able to open up an airfield rapidly in any environment, friendly or hostile, we’re extending the reach of airpower.”

RELATED

Contingency response units regularly build bare bases and conduct austere airfield operations within a 24-hour time period, but the exercises are usually simulating a permissive environment, Air Forces Europe said in its release.

“This is the first time we’ve really done this in a contested environment, where we actually have a threat out there that we are trying to address with security forces,” Hester said. “It’s something new for us where everybody goes out the door with a weapon. Everybody is a base defender and can provide that security 24/7.”

Although all participants were American, the training at Contested Forge isn’t just about U.S. capabilities; it’s also a boon for the NATO alliance as a whole.

“This training allows us to be a credible force for our allies,” Lt. Col. Leonardo Tongko, 435th CRS commander, said. “It is to assure them we can provide support, deter and defend them from any threat in a moment’s notice — we have the capability to build, sustain and defend airpower.”

However, Contested Forge isn’t really a new way of conducting air warfare, according to Lt. Gen. Mark Kelly, commander of the 12th Air Force.

Air-oriented militaries trace their origins to World War I, a time when they were also forced to be self-sufficient, self-sustaining and self-defending, Kelly told a crowd of Air Force leaders at the 2018 Air, Space and Cyber Conference in Washington, D.C., in mid-September.

Kelly used the example of World War I German Air Force commander Manfred von Richthofen’s “flying circus," a mobile squadron of forward-deployed aircraft and crew that maintained air superiority for German ground forces when and where it was able to put down tent stakes.

That dislocated German squadron, making due with few resources while facing new and violent threats — in their case, chemical warfare agents — provides a good historical reference for what will be expected in a modern fight with a near-peer adversary.

“Richthofen didn’t build this circus just because it was fun to drive around," Kelly said. “He was only constrained by the rail networks of the Western Front ... his logistics lines. If he had the force he needed, he could have built permanent bases, but he didn’t."

"That’s probably the best snapshot I can give you” of what the Air Force is building toward, Kelly added.

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.