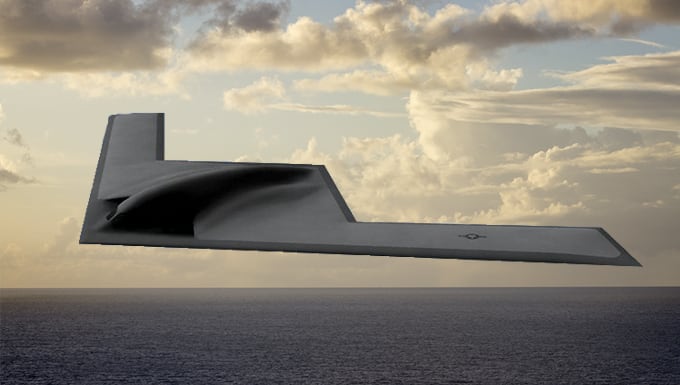

WHITEMAN AIR FORCE BASE, Mo. — Being a B-2 pilot means experiencing the rush of takeoff and the pressure of weapons drops while flying in the nation’s only stealth bomber. But it also involves having to manage nap times with your co-pilot during daylong-plus flights.

“After you do a few [long-duration flights], anything under 20 hours doesn’t seem like a big deal,” said Capt. Chris “Thunder” Beck, a former B-52 pilot who recently graduated from B-2 pilot training school. Beck spoke to journalist and Defense News contributor Jeff Bolton during a visit to Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri.

Beck has yet to conduct a long-endurance flight in the B-2 Spirit, the stealth bomber produced by Northrop Grumman and introduced to the U.S. Air Force’s inventory in 1997. However, he got used to long missions while flying in the B-52, with one especially extended haul taking him from Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana, to Japan, and then back.

Click here for more from the special report on the U.S. nuclear enterprise.

“My personal record is 33 hours for my longest duration, but you just really got to take it from a big-picture standpoint, what you’re trying to achieve — you and your crew — and that’s what you have to focus on. It helps the time go by,” he said.

RELATED

The B-2 is the only bomber in the U.S. inventory able to penetrate enemy territory to drop nuclear bombs, and still survive. Only 21 were produced, and all 20 operational jets are based at Whiteman AFB.

To prepare for the types of missions that would take them beyond an adversary’s border, B-2 crew training involves traveling from America’s heartland to the other side of the globe.

Beck said he tries to stay awake for the majority of a long flight on the B-52 so he can be ready to perform any task needed. But B-2 pilots have less of a choice in that respect. The B-52 is flown by a five-person crew — two pilots, two navigators and one electronic warfare officer. On the B-2, all tasks are shared between the two pilots, leaving less time for rest.

“You just have to identify what the crunch points are going to be. What’s going to be the most important thing to do?” said Capt. Mike Haffner, a B-2 pilot with the 13th Bomb Squadron, who manages the aircraft simulators.

“When you get started in that mission, [it’s important] to not get lulled into a false sense of security because you feel like you have 12 hours or more to get over to the target area,” he said. “You’ve got to be productive and get things done, so you can start taking turns taking naps and getting ahead of that, because as soon as you get behind the power curve, it's kind of hard to recover.”

RELATED

Whiteman Air Force Base maintains a staff of doctors and physiologists that specialize in how protracted flying can impact the human body. These officials help new pilots learn techniques to improve their performance over long-endurance missions and update experienced pilots with new information about how to prevent fatigue.

“There is a way you can shift that circadian rhythm back and forth by getting the appropriate amount of sleep, shifting your sleep schedule and even modifying diet,” said Capt. Caleb James, a doctor with the 509th Medical Group.

For especially long missions, James said doctors will prescribe medication “in the event that those members need that little bit of extra push to help them stay focused on the mission.”

At the outset of a B-2 mission, most pilots will spend “a lot of time” planning missions as well as learning how to balance obligations like takeoff, weapons activity and aerial refueling with rest, said Lt. Col. Niki “Rogue” Polidor, a B-2 pilot and the 509th Bomber Wing’s chief of safety.

“When you’re faced with a 24-hour mission, or a long-duration mission, you really get into the details of who is going to do what task, and how we’re going to manage our sleep,” she said. The timing of every task needs to be set in advance “so that we’re both prepared to be in the seat, ready to go, for all the air-refueling and the weapons activity, and then of course landing.”

Usually, pilots can work in naps, each numbering a couple hours, but “it depends on our route of flight, where our refuelings are place along that route, and where our weapons activity is,” Polidor said.

Apart from that, every pilot has their own common-sense methods to ensure they stay sharp on long-haul flights.

“The day before, I don’t want to eat anything too extravagant and try to get to bed early,” Haffner said. “When you wake up, just roll back over and go back to bed as long as you can."

Beck noted the importance of staying hydrated and said he brings bottles of water and Gatorade aboard flights.

Haffner brings toiletries, spare clothes and light snacks.

“I kind of relate it to driving on a road trip,” he said. “You're stopping by the fast food restaurant, and you get the double cheeseburger and the fries and the shake and everything, and you're going to put yourself to sleep. But if you don't eat anything, you're also going to feel miserable. So you’ve got to find that happy middle point.”

Environmental cues can also cue the body to stay awake or sleep. For example, Beck’s 33-hour B-52 flight to Japan followed the sun, giving the crew only a few hours of darkness.

“Your mind doesn't know what to think at that point. You're just awake,” Beck said, adding that situations like that can cause the crew to lose track of time.

“You’re very thankful when you land, I’ll say that."

Defense News partnered with independent journalist and long-time radio personality Jeff Bolton for a multimedia report that takes an up-close look at the U.S. nuclear enterprise by way of Bolton’s exclusive flights on military strike platforms and interviews with the leadership and military staff that support nuclear operations and missions.

Valerie Insinna is Defense News' air warfare reporter. She previously worked the Navy/congressional beats for Defense Daily, which followed almost three years as a staff writer for National Defense Magazine. Prior to that, she worked as an editorial assistant for the Tokyo Shimbun’s Washington bureau.