PHILADELPHIA — On Sept. 28, 1918, in the waning days of World War I, more than 200,000 people gathered along Broad Street in Philadelphia for a parade meant to raise funds for the war effort.

Among the patriotic throngs cheering for troops and floats was an invisible threat, which would be more dangerous to soldiers and civilians than any foreign enemy: the influenza virus.

Officials went ahead with the parade despite the discouragement of the city health department about the ever-spreading virus. Within 72 hours of the parade, all the hospital beds in Philadelphia were full of flu patients. Within six weeks, more than 12,000 people died — a death every five minutes — and 20,000 had died within six months.

Despite the human toll, there has been no memorial or public remembrance of flu victims in the city.

Until now.

The Mutter Museum, known for its collection of organs preserved in jars, deformed skeletons and wax casts of medical maladies, is launching new permanent exhibit on the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic in Philadelphia.

“Spit Spreads Death” will open on Oct. 17, and will feature interactive displays mapping the pandemic, artifacts, images and personal stories.

"It's still referred to by some historians as the forgotten pandemic, because how many Americans are conscious of it today?" said Robert Hicks, the museum's director.

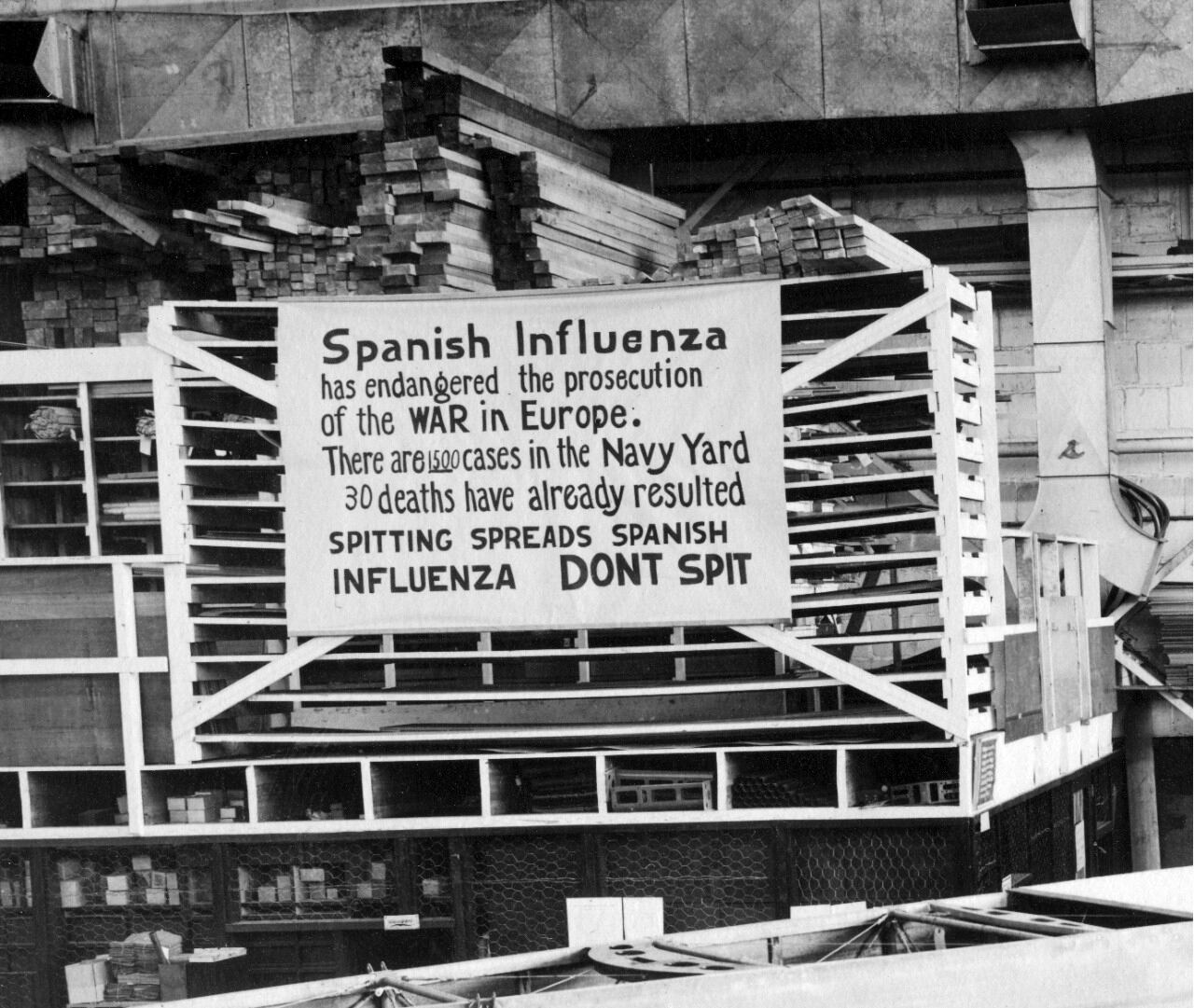

The exhibit takes its name from health department signs that popped up around the city as the pandemic spread.

Ahead of the exhibit’s launch, the museum will present a parade Saturday along the same stretch of road where the ill-fated Liberty Loan Parade took place.

A sort of moving memorial, the parade will feature about 500 members of the public honoring victims of the pandemic, four illuminated floats and an original piece of music performed by Grammy-winning choir “The Crossing.”

"The parade has turned into an interesting commemorative act," said Matt Adams, co-founder of Blast Theory, the artists' group creating the parade.

Anyone can sign up to participate and can choose the name of an actual flu victim to honor while marching. Marchers will be given a sign with the name of the person they chose and will move along the parade route flanked by the illuminated sculptures.

Members of city’s public health community have been urged to join in.

"This is all about the process of remembering what the risks are in public health, because that is a crucial way for us to stay safe today," he said.

More U.S. soldiers died from the flu than from battles in Europe during the war.

It was called the Spanish flu at the time because Spain was neutral during the conflict and had no restrictions on the press, and could therefore report the outbreak freely, said Nancy Hill, special projects manager at the museum.

The general public in much of the U.S. was uninformed about the virus because of the crackdown on news and any speech deemed unpatriotic. Speaking of soldiers dying from the flu fell into that category.

About 500 million people, or one-third of the world's population, became infected with the virus. An estimated 20-50 million died around the world, with about 675,000 flu-related deaths in the United States.

Troops moving around the globe in crowded ships and trains helped the deadly virus spread as the war dragged on.

The exhibit itself will include interactive displays that allow people to explore their own neighborhoods to see how the flu hit their street, and even their own homes.

Among the most poignant artifacts is a selection of Christmas gifts that a woman named Naomi Whitehead Ellis Ford purchased for friends and family, all fitted with handwritten personal notes to the intended recipients.

But they were never handed out, because she passed away from the flu on Oct. 21.

Hicks hopes visitors take away a sense of the scope of the pandemic and see how the city came together to help each other, and to be vigilant — getting vaccines, taking common-sense health care measures and staying informed.

The museum even threw a health fair in a south Philadelphia neighborhood, offering everything from flu shots to Narcan training.

“It is too easy in the United States to forget,” Hicks said.

“Cholera, typhus, typhoid fever all mean nothing to most Americans today, but President Lincoln’s son was killed by typhoid fever. From the high and mighty to those whose names aren’t remembered, these diseases were commonplace. The fact that measles is back again is a great reminder: These diseases don’t go away.”