Former Spc. Jim McCloughan had just graduated from college when he got a letter from the U.S. government in May 1968. He was to report for a physical.

Then 22, the Michigan native had just signed a contract to teach and coach sports at his high school alma mater, but the Defense Department had other ideas.

"They told me they would like me to join the United States Army," he told Army Times in a Thursday interview.

McCloughan, now 71, figured he'd do his two years and go back home, but he ended up doing a lot more: In a two-day battle while deployed to Vietnam, his actions as a combat medic earned him the Medal of Honor, the military's highest valor award.

"This medal is all about love," he said. "It’s a love story so deep in my soul that it’s truly immeasurable."

It was the morning of May 13, 1969, and C Company, 3rd Battalion, 21st Infantry, 196th Light Infantry Brigade, Americal Division, had come under small arms fire while assaulting into an area near Tam Ky and Nui Yon Hill, according to the official award narrative.

The enemy shot down two helicopters, one of which crashed about 100 meters from McCloughan's position. A squad went out to bring the pilot and crew back to the company's position.

"When the squad and crew members reached the company perimeter, a wounded soldier was laying on the ground, too injured to move," the narrative reads. "McCloughan ran 100 meters in an open field through the crossfire of his company and the charging, platoon-sized North Vietnamese Army. Upon reaching the wounded soldier, Pfc. McCloughan shouldered him and raced back to the company, saving him from being captured or killed."

Hours later, his platoon went out to scout the area near Nui Yon Hill, where they were ambushed. McCloughan got into a trench, then peered over the edge, spotting two soldiers huddled near a bush without weapons.

"With complete disregard for his life and personal safety, McCloughan handed his weapon to a fellow warrior, leaped on the berm of the trench and ran low to the ground toward the ambush and the two Americans," the narrative reads.

As he checked them for wounds, a rocket-propelled grenade exploded and peppered him with shrapnel. He pulled the Americans back into the trench, then ignored an order to stay put, running four more times into the kill zone to find more wounded soldiers.

"Bleeding extensively, McCloughan treated the wounded and prepared their evacuation to safety," the narrative reads. "The Americans were heavily outnumbered by NVA forces. Knowing a medic would be needed, he refused his evacuation and remained at the battle site with his fellow soldiers."

The next day, another platoon was ambushed as they moved toward Nui Yon Hill. Their medic was killed, leaving McCloughan the only doc in the company.

"Through intense battle, McCloughan was wounded a second time by small arms fire and shrapnel from an RPG while rendering aid to two soldiers in an open rice paddy," according to the narrative.

Two NVA companies and 700 Viet Cong soldiers descended upon their position on three sides, prompting McCloughan to run into the crossfire multiple times to extract the wounded.

"His relentless courageous action inspired and motivated his comrades to fight for their survival," the narrative reads. "When supplies ran low, McCloughan volunteered to hold a blinking light in an open area as a marker for a nighttime resupply drop. He remained steadfast while bullets landed all around him and RPGs flew over his prone, exposed body."

The next morning, McCloughan destroyed the RPG position with a grenade, while continuing to fight enemy soldiers and care for wounded American troops, organizing the casualties for extraction when the sun came up.

"He then collapsed from dehydration and total exhaustion," the narrative reads. "McCloughan is credited with saving the lives of 10 members of his company."

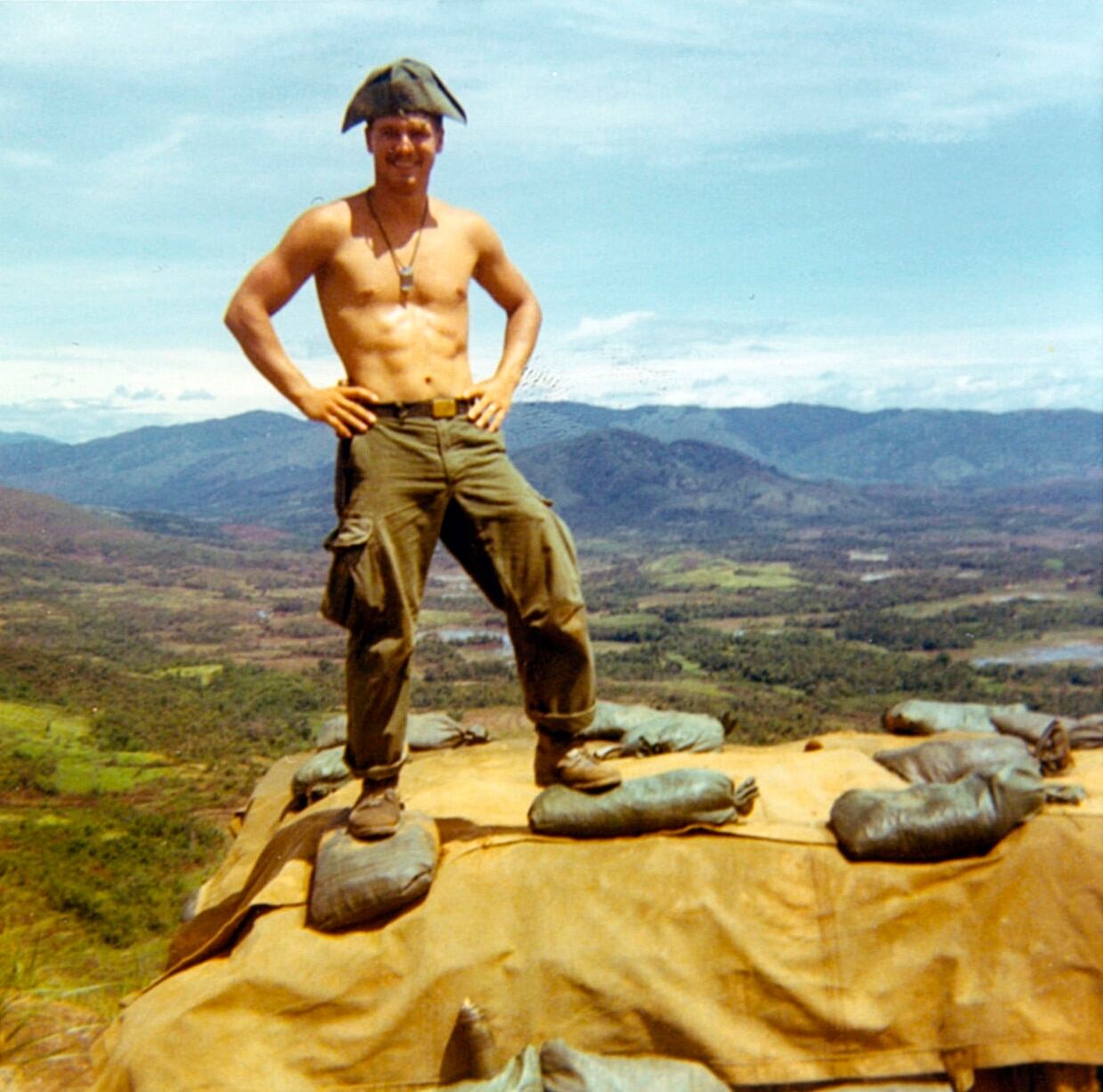

In this 1969 photo provided by James McCloughan, the former Army medic stands on a bunker in Vietnam.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of James McCloughan via AP

Looking back

McCloughan can't be sure why the Army thought he'd make a good combat medic, but he has an idea. As a student at Olivet College in Olivet, Michigan, he'd taken classes in kinesiology, physiology and advanced first aid.

"I think they thought that maybe if I knew how to tape up an ankle, and had gone through those strapping classes that I’d gone through, that I might have a little bit of a heads up on some things that I was going to be facing," he said.

The classes did help prepare him, he added, but his stamina and determination came from his favorite hobbies.

"I wouldn’t say that I wasn’t scared, because everybody’s scared. But I’ve always said that I owe it to high school and college football and college wrestling," he said. "Those sports prepared me for the mental discipline I need in those situations, to go out and do my duty."

On May 13, 1969, he said, all he cared about was getting everyone home.

"The love for my men. The fact that I was going to bring as many of them home as I possibly could, hoping that I didn’t lose my own life in the process," he said. "There were certain situations that, if we would have had the best doctor in the world, we would not have been able to save them. So I’ve come to peace with that part of it."

Four months later, his platoon leader told McCloughan he'd put him in for the Distinguished Service Cross.

"They had told him that I was, ‘Only a PFC and PFCs don’t get that medal,’ so they suggested that he put me in for the Bronze Star," he said.

McCloughan did receive the Bronze Star with "V" device. He also got an early release from the Army because he had a job lined up, so he went back to Michigan and his teaching career — first at Olivet College, then to South Haven High School, where he'd first signed that contract after college graduation.

He spent decades as an educator in Michigan, the way he'd always intended, though Vietnam was always in the back of his mind.

"You can’t escape something like that when it happens in your life. I became a very hard worker. I worked long hours and I kept my mind off of it," he said. "And that was just great until I retired. And then when I retired in 2008, some of those thoughts came creeping back in."

He only told two people that he'd been up for the DSC: his father and his uncle. The year McCloughan retired, his uncle called him up and said he had an appointment with local Republican congressman Rep. Fred Upton.

"I said, what for? And he said, 'To get that medal that you should have gotten 40 years ago,' " McCloughan said.

Major upgrade

That meeting set off a chain of meetings with Michigan congressional members, including Democratic Sen. Gary Peters, Democratic Sen. Debbie Stabenow and former Democratic Sen. Carl Levin, while his former platoon leader, Randy Clark, filed the paperwork on the Defense Department side.

On Oct. 5, Stabenow called McCloughan to tell him that the award packet had gone in front of then-Defense Secretary Ash Carter, who recommended the nomination be upgraded to Medal of Honor. But Congress needed to make an exception to give him the award more than five years after the action, per policy, so Stabenow and her colleagues wrote it into the National Defense Authorization Act that President Obama signed on Dec. 23.

"I want to thank those who were so persistent — the men from my company, Lt. Clark, Ashton Carter, Fred Upton, Debbie Stabenow, Gary Peters, Carl Levin — all of those individuals who made this particular opportunity possible," McCloughan said. "They were relentless."

But it still wasn't over. Then-Army Secretary Eric Fanning signed off on the award Dec. 27, but by then, it was too late for the Obama administration to schedule and hold a ceremony.

"My advice to anyone is, have confidence, sit back, wait for the process to happen," McCloughan said. "And when it does, whatever the good Lord has in mind, he has in mind."

So McCloughan waited, he said, without any updates. Until May 25, when he got a call telling him to be by the phone on the afternoon of May 30 for an important government official.

"That’s when we spoke with the president," he said. "He said that he was looking forward to meeting us, and we said the same."

McCloughan is scheduled to receive his medal on July 31, just a few days after the 196th Infantry Brigade's reunion.

"I will be able to invite them, and yes, there are quite a few of them around," he said. "Of the 32 of us that walked out of that battle, I’ve reconnected with 20 of them."

In a photo from Friday, June 9, 2017, former Army medic James McCloughan kneels next to a statue presented to him by a fellow soldier in South Haven, Mich.

Photo Credit: Carlos Osorio/AP

Medal of Honor recipients are regularly asked to become something like ambassadors for the Army, speaking at and attending official events. McCloughan said he is excited to participate.

"The next few years will challenge me to make sure that I give that medal the proper honor, and that I use that medal to continue to serve others, and to continue to love those that need to be loved," he said. "This medal I’m only going to be wearing for the 89 men that went into that battle."

He's also looking forward, he said, to being reunited with the Army family to spread a positive message.

"Any time I can spend time with my brothers and sisters who fight for this country and fight for freedom, it’s a positive thing," he said. "I hope that this brings some positivity to the United States of America. We’re at a time now when we really need to head back in a positive direction."

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.