Air Force officials are betting that a few tweaks to longtime requirements for prospective pilots and other officers can have a big impact on diversity in the force.

As it tries to mirror the demographics of the United States at large, the Air Force says certain skills, benchmarks and testing strategies are outdated and don’t adequately predict future success.

The service has made multiple changes to the pilot selection process this year that should grow the pool of qualified applicants, particularly in underrepresented minority groups, without changing the standards needed to become an officer and an aviator. An updated policy memo quietly rolled out in March to outline the new rules.

RELATED

The Air Force will now make officer hopefuls wait 90 days rather than 150 days to retake the Air Force Officer Qualifying Test, the seven-decade-old multiple-choice exam used to gauge a person’s verbal, quantitative and academic abilities. Cadets can retest only once.

Cutting that wait time in half will give cadets the chance to take the standardized AFOQT multiple times before make-or-break moments like competing for field training, a commissioning spot or at ROTC boards, the service said. First-time test-takers can study together from now on as well, another change from past rules.

A similar change took effect for the Test of Basic Aviation Skills, halving the retest wait time from 180 days to 90. A person can take the TBAS up to three times, as long as they get a waiver from their wing commander or equivalent boss for the third try.

The Air Force is also ditching its policy of using only the test scores from the most recent attempt. Now, cadets will be judged on their highest composite scores from any testing attempt. Test-takers need to score at least 15 on the verbal portion and 10 on the quantitative portion, plus other minimum scores needed for those looking to become a pilot, combat systems officer or air battle manager.

“Super-scoring” can help cadets who are stronger on some subjects than others, taking away the pressure of having one shot to pass a section in which they struggle.

“The super-scoring system is a great equalizer for English-as-a-second language cadets because they can focus on the verbal portion of the AFOQT after they have a passing score on the quantitative portion of the test,” the Air Force said.

RELATED

For example, Spanish-speaking cadets with a strong background in science and technology, usually score above average when they take the math-focused portion of the AFOQT for the first time, but then fail the verbal portion because of their language barrier, the Air Force said.

“Allowing the highest AFOQT composite score will allow ESL cadets to focus solely on the verbal portion of the test, thus increasing the overall pass rate,” the service argued.

Overall highest composite scores will also be fair game when applying for rated jobs like pilot positions, a reversal from earlier policy. The Air Force hopes that can help Hispanic and other cadets who are non-native English speakers get into jobs that were previously out of reach.

The Air Force’s decision to update its policy is a great win and a good example of how advocacy and collaboration with the military can lead to meaningful change, said Edward Cabrera, a retired Air Force colonel who sits on the board of directors of the Hispanic Veterans Leadership Alliance. Younger officers raised the AFOQT issues to him as low-hanging fruit for improvements, the former F-16 Fighting Falcon pilot and test wing vice commander told Air Force Times.

It’s unclear how many people for whom English is not their first language typically try to become an officer, like Puerto Rican engineers. It could potentially be a significant number — hundreds of prospective airmen — that can snowball over time, Cabrera said.

He believes the onus would be on a newly admitted airman to bring their English up to speed with everyone else’s. But pilots and air traffic controllers should have little problem, he said, as English is the universal language of aviation communications.

Scores from both the officer qualifying test and basic aviation skills test are combined with a person’s flying hours to create a score that indicates their readiness for manned and unmanned aircraft pilot training.

Even the flight time requirement is getting another look. The Air Force wants to use digital flight simulators to overcome the socioeconomic hurdles posed by real-life aviation training, available to those who have that opportunity nearby and the funds to pay for it.

“Modern testing methods can gauge a brain’s orientation on being able to be as successful in an aviation environment, and that’s the aptitude that we want a measure of, more so than what experience you’re able to learn on your own,” Air Education and Training Command boss Lt. Gen. Brad Webb told reporters in a call last month.

To help overcome that hurdle, the U.S. Air Force Academy and ROTC offer free ground and flight training to improve students’ chances at snagging pilot’s wings.

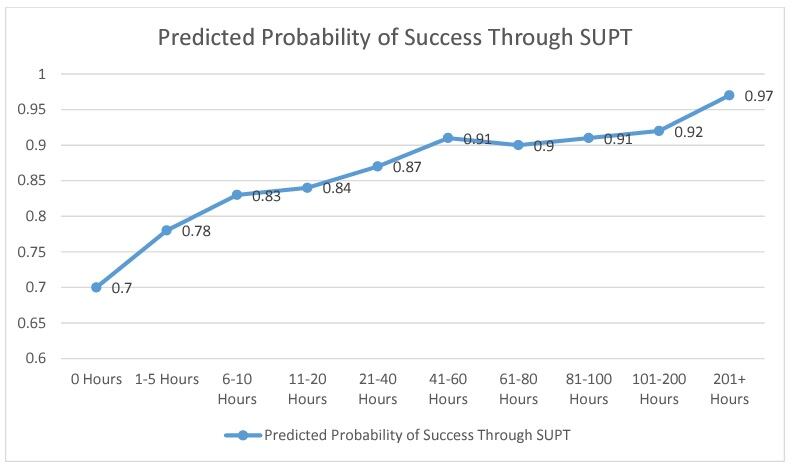

Going forward, the Air Force will only take into account someone’s first 60 hours in the cockpit when using flying hours as the second-largest part of their aptitude score.

More hours than that don’t end up having much bearing on a candidate’s chances of success, according to Katie Gunther, chief of strategic research and assessment at the Air Force Personnel Center.

Only considering the first 60 flight hours on an application would result in about 70 more qualified Hispanic candidates, 47 more women and 26 more Black candidates over 12 years, an Air Force study found last year.

Still, “the additional selectees over the 12-year period would have been selected at the low end of ability as measured by the [pilot candidate selection method], thus adding risk to the Air Force of selecting candidates who may not be as likely to succeed in pilot training as their higher-ability counterparts,” the report said.

The changes are the result of work done by the 2020 racial disparity review of Black airmen’s experiences in the service, the Hispanic Empowerment and Advancement Team and the Pilot Selection Process working groups, and others to reassess existing hurdles to advancement within the Air Force and Space Force.

A six-month progress report on that first racial disparity review, published Sept. 9, cautioned it may take a while to see the effects of new policies take hold.

Given that pilots and other airmen in rated and combat operations jobs are heavily favored for opportunities to progress up the career ladder, the Air Force said in the progress report, service leadership will remain dominated by white and male airmen until the pipeline in those fields grows more diverse.

“While there is a lot of good work being done, we still have much work to do in addressing racial disparities,” the service said.

Rachel Cohen is the editor of Air Force Times. She joined the publication as its senior reporter in March 2021. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Frederick News-Post (Md.), Air and Space Forces Magazine, Inside Defense, Inside Health Policy and elsewhere.