An Air Force inspector general review into racial disparities found widespread differences, year after year, in how Black airmen are treated as opposed to airmen of other races.

The investigation, which the Air Force released Monday, studied how Black airmen are affected by law enforcement apprehensions, criminal investigations, military justice, and administrative separations. It also reviewed which career fields Black airmen tend to be placed into, promotion rates, professional military educational development, and leadership opportunities.

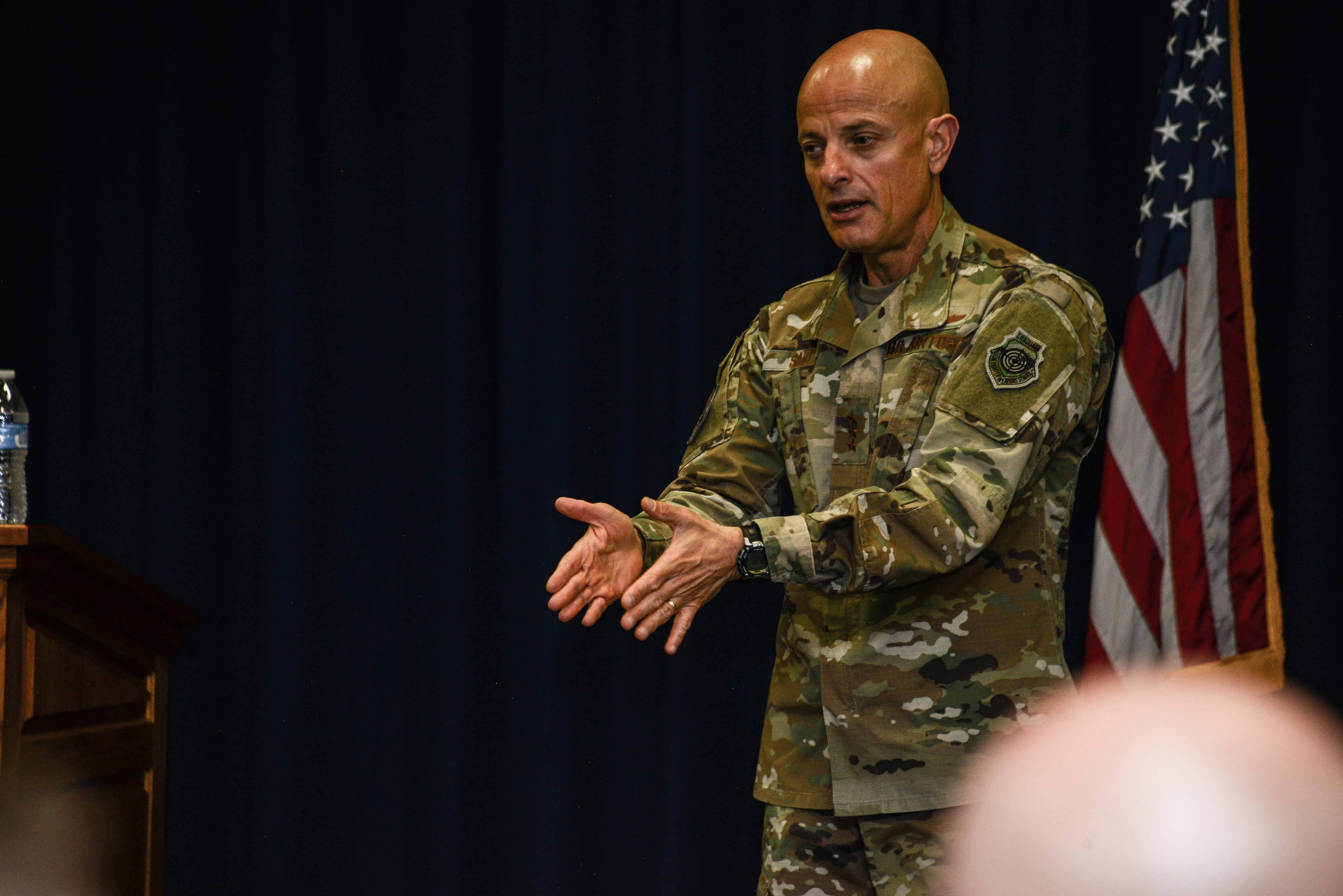

The result, said Air Force Inspector General Lt. Gen. Sami Said, is clear: Across the board, and consistently over time, Black airmen were disproportionately negatively affected in each category, as compared to their overall representation in the Air Force.

The Air Force launched its effort to study racial disparities, and to survey airmen about race and their experiences in the service, in June, after the death of George Floyd sparked nationwide protests and movements to root out racial bias and inequality nationwide. The review also covered civilian personnel and Space Force guardians, as well as service members across the total force, both officers and enlisted.

The report that resulted found that enlisted Black airmen were 72 percent more likely than their white counterparts to receive non-judicial punishments from their commanding officer, and 57 percent more likely than white service members to face a court-martial, the report said.

Young Black enlisted airmen are almost twice as likely as their white counterparts to be involuntarily discharged for misconduct. And Black airmen are 1.64 times more likely to be suspects in Office of Special Investigations criminal cases, and twice as likely to be apprehended by security forces, the report said.

These results confirm the findings of a report the military advocacy group Protect Our Defenders released in May, which found the military justice system disproportionately punished Black airmen more frequently than other airmen.

The racial disparities hurting Black airmen also became evident at several points along their career paths, the report said. For example, on the enlisted side, Black airmen enlist at higher rates than would be expected, as compared to their proportion of the overall eligible U.S. population.

But as their careers develop, Black airmen find themselves disadvantaged in subtle, but crucial ways. Black airmen are underrepresented in operational career fields such as pilots, and overrepresented in support career fields, the report said.

Because key career development opportunities, such as the best chances at leadership and education, are more frequently offered to airmen in operational fields, those who are in support jobs tend to suffer.

What’s more, over the past five years, Black officers have been overrepresented in their nominations to attend professional military education, the report said — but when the actual selections for PME classes are made, Black officers are underrepresented. That gap is especially acute for senior developmental education, as opposed to intermediate developmental education, the report said.

When it comes to promotions at key points in airmen’s careers — for enlisted, to staff, technical or master sergeant, and for officers, to major, lieutenant colonel and colonel — Black airmen again find themselves at a disadvantage. The report found they are regularly promoted to those ranks at disproportionately lower rates than would be expected. And when Black airmen don’t make colonel or master sergeant, for example, that means fewer Black airmen who can become general officers or chief master sergeants, resulting in a whitening of the service’s upper ranks.

Air Force Times in 2016 studied six years of promotion data obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, and similarly found Black airmen, as well as airmen of other minority races, were consistently selected for promotion at lower rates than white airmen.

RELATED

Said said that the report’s conclusions about disparities were based solely on the hard data researchers collected, and not anecdotes.

But the personal experiences shared by thousands of Air Force and Space Force personnel helped researchers confirm and understand the real-world effects of the disparities it was finding.

The two-week survey drew an overwhelming response, with more than 123,000 people sharing their thoughts and observations about racial inequality and disparities.

Those responses, Said said, tracked very closely with the results of the data. Service members and civilians also shared more than 27,000 single-spaced pages of comments with their experiences and observations. And investigators conducted 138 group discussions in person with personnel across all major Air Force commands and the Space Force.

“The voice of the airman … was cross-cutting, it was overwhelming in volume coming to us, and it was multifaceted,” Said said. “And without prompting at all on the themes that emerged from the survey … lo and behold, we found very close matches, almost identical. And in a couple of areas, we uncovered new themes.”

Said stressed that this report was designed to be “surgically-scoped” on Black airmen and their experiences in justice and career development to make sure it was thorough and could be completed quickly.

“If you don’t know where there’s potential smoke, and you don’t know if it’s smoke or dust, you’ll kind of wander all over the place,” Said said.

But it won’t be the Air Force’s last word on diversity. More work needs to be done to investigate disparities in how other groups, such as women, are treated in the Air Force.

Finding out what is causing these differences will be complicated and take time. The Air Force could not conclude in this report whether, or to what extent, bias or racial prejudice played a role in creating the uncovered disparities.

But thousands of Black airmen and civilians overwhelmingly spoke up in survey responses and roundtables about their experiences of “issues ranging from bias to outright racial discrimination,” the report said. And such isolated racist acts could contribute to the racial disparities investigators identified, the report said.

The racial disparity issue is most acute among pilots in the Air Force. Out of 15,000 pilots in the Air Force, only 305, or 2 percent, are Black, the report said.

Because the Air Force often selects leaders — particularly high-ranking leaders up to and including chief of staff — from the ranks of pilots, that can result in relatively few Black leaders. The Air Force’s current chief of staff, fighter pilot Gen. Charles “CQ” Brown, is the first Black service chief in U.S. history.

There are several factors that could be limiting the number of Black cadets and airmen who seek to join, or are accepted to, pilot training.

For example, the report said, an ROTC representative that visits historically Black colleges said some Black cadets aren’t interested in the 10-year service commitment required to become a pilot. That representative said those cadets were the first in their families to go to college, and instead planned to serve four years and then get a higher-paying job in the private sector, which is how their families viewed success.

When selecting candidates for pilot training, the Air Force also gives extra points to applicants who already have flying hours under their belts. But applicants who come from lower socio-economic backgrounds may not have had the means to pay for flying lessons privately, and lose that potential advantage.

A recruiting unit stood up in 2018, Air Force Recruiting Service Detachment 1, is trying to help fix that problem. Detachment 1, which is meant to try to improve the representation of women and minority airmen in the pilot corps, is holding summer flight camps for underrepresented groups to teach them to fly and earn hours to improve their Pilot Candidate Selection Method scores.

The Air Force has also created a Rated Preparatory Program, which seeks to help officers cross-train into rated career fields by giving them basic aviation experience and up to 10 hours of flying.

These differences can also be self-perpetuating. With so few Black pilots around, it’s hard for young Black men and women to see them and realize that it’s a career path they too could take, the report said.

Air Force Secretary Barbara Barrett has now ordered agencies to come up with plans to figure out the root causes for these problems and correct them, within 60 days. Those plans must include specific changes to policy, processes and procedures, and how those changes will affect the racial disparities.

The IG’s office will keep watching these issues and release a progress report six months from now measuring what the Air Force has done, and will also do a full review annually.

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.