The Air Force could have prevented a former airman from buying a weapon and committing a mass shooting last year had investigators followed proper protocol, according to a Pentagon investigation of the incident released this week.

The investigation casts doubt on the capabilities of Air Force Office of Special Investigations agents and the training of ordinary security forces airmen, according to the Defense Department Inspector General report, released Dec. 6.

The findings, and a follow-up review across the DoD, could have implications across all the armed forces investigative arms.

“We are currently conducting a follow-up review to assess the progress throughout the DoD in ensuring that all fingerprints required to be submitted to the FBI are in fact submitted,” DoD IG officials said. “This review will also assess whether DoD law enforcement agencies submit DNA to the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System, as well as criminal history data, mental health information, and sex offender information, as required.”

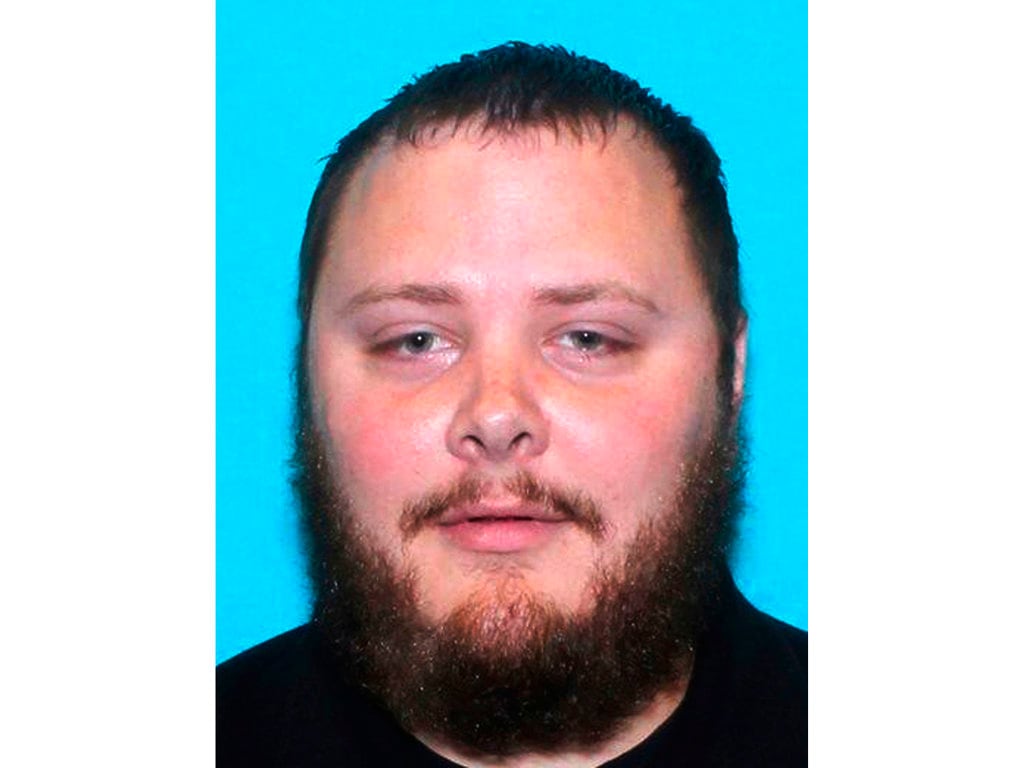

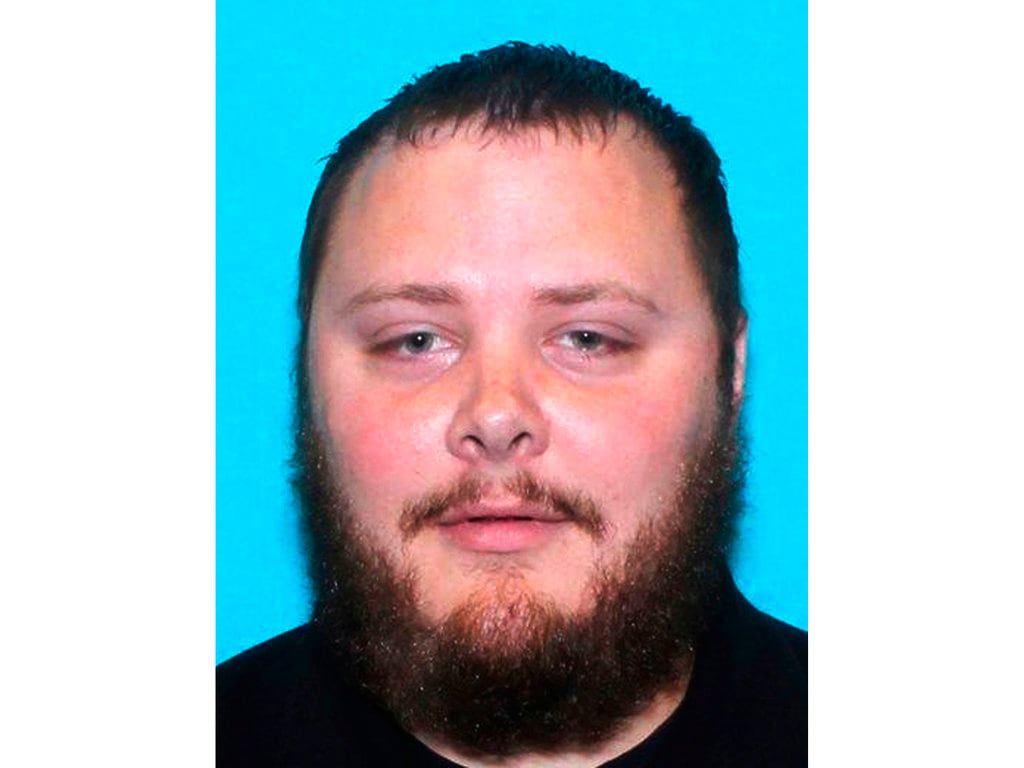

On Nov. 5, 2017, former airman Devin Kelley shot and killed 26 people and wounded 22 others at the First Baptist Church of Sutherland Springs, Texas. After being shot by citizen responders, Kelley fled from the church in his vehicle and later died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Kelley was able to purchase a firearm from a federally licensed dealer even though he had a disqualifying conviction.

Kelley, who enlisted in 2010, served as a logistical readiness airman at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico. In 2014, he was discharged from the Air Force after being convicted of assault. Because of that conviction, the Air Force should have sent his fingerprints and final disposition report to the FBI Criminal Justice Information Services Division.

“If Kelley’s fingerprints were submitted to the FBI, he would have been prohibited from purchasing a firearm from a licensed firearms dealer,” DoD IG officials said in their 131-page report.

RELATED

The DoD IG conducted an investigation into Kelly’s actions to examine why the Air Force did not provide his fingerprints to the FBI, as was required. The office’s report found that the service had four different opportunities to submit the fingerprints, all of which they failed to do.

AFOSI Special Agents failed to follow proper training and provided little reasoning behind why they did not submit the information, other than the large case-load being handled by their office, the turnover of staff and the inexperience of newer agents.

“These factors provide context for the failures," investigators said. “However, they do not excuse the failures. The investigators and confinement personnel had a duty to know, and should have known, the DoD and USAF fingerprint policies, and should have followed them. The failures had drastic consequences and should not have occurred.”

The Office of the Secretary of the Air Force said "the failure in reporting Kelley’s criminal history was not an isolated event unique to this case or to Holloman Air Force Base where the investigation unfolded.”

Lack of compliance with reporting requirements across the services was highlighted in multiple DoD IG audits that took place prior to the Texas shooting. Some corrective actions were implemented, but they were not timely or sufficient to achieve compliance across the force.

Immediately following the mass shooting last year, the Air Force directed a review of all criminal history reporting requirements.

This review, which was completed in late December 2017, generated 21 recommendations to correct deficiencies in criminal history reporting, 20 of which have already been completed, Air Force spokesman Ann Stefanek said in a statement. The remaining recommendation, primarily focused on enhancing efficiency, will be completed in July.

The Air Force intends to correct all legacy case files going back to 1998, Stefanek added.

The first opportunity to submit fingerprints occurred in 2011. Kelley had already failed out of tech school to become a network intelligence analyst, and was reclassified to be a traffic management apprentice. During this time, he married a former classmate with a son from a previous relationship.

Kelley repeatedly hit his new stepson and wife. After the boy was hospitalized for various injuries, an investigation was initiated in June 2011.

AFOSI Detachment 225, at Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico, conducted the investigation.

RELATED

This was the first opportunity to collect Kelley’s fingerprints. But Det. 225 leadership did not create a note in the investigative case file stating that the fingerprint card had been reviewed in accordance with AFOSI policy.

As the investigation progressed, Kelley returned to work and repeatedly received letters of counseling and reprimand from leadership for his failure to attend training classes and for his use of a cellphone during duty hours, as well as verbal confrontations with superiors.

The 49th Security Forces Squadron Office of Investigations conducted a subject interview with Kelley in February 2012 related to an assault on his wife, which violated Article 128 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

Investigators wrote a report following the interview, which said Kelley must turn over a handgun he purchased at the Holloman base exchange to his acting first sergeant, who then turned it in to security forces.

“This is the second opportunity to collect Kelley’s fingerprints,” the DoD IG report reads.

Kelley continued to have problems at work, and with his UCMJ hearing approaching, he was ordered to confinement in June 2012.

Kelley’s commander prepared the pre-trial confinement package, which included a memorandum stating that the commander was convinced Kelley was “dangerous and likely to harm someone if released.” The commander also cited an internet search by Kelley for body armor and firearms as further justification for the pre-trial confinement.

Kelley was identified as a flight risk and he was ordered into confinement at the 49th Security Forces Squadron confinement facility.

In June 2012, AFOSI special agents conducted another interview with Kelley. The record from that encounter states that his fingerprints were collected, but there were no corresponding fingerprint cards in the case file, according to the DoD IG.

“This is the third opportunity to collect Kelley’s fingerprints," DoD IG officials said.

The final opportunity came in November 2012, when Kelley was convicted of assaulting his wife and her son during a general court-martial. He was reduced in rank to E-1, ordered into confinement for 12 months and given a bad conduct discharge.

Kelley was confined to Holloman before transfer to a larger facility. Air Force Corrections System policy requires all post-trial inmates to have their fingerprints collected and submitted to the FBI during in-processing.

However, there is no record of the confinement facility collecting or submitting Kelley’s fingerprints, according to the DoD IG. This was the fourth opportunity for the Air Force to collect Kelley’s fingerprints and the first opportunity to submit a final disposition report for his criminal history.

In December 2012, AFOSI received an AF Form 1359, stating that Kelley’s conviction is a crime of domestic violence and requires DNA processing. Receipt of those forms also requires AFOSI to submit Kelley’s fingerprints and final disposition to the FBI, if not already submitted.

This was the second opportunity for the Air Force to submit the disposition of his conviction. But it did not occur, even though the special agent in charge of Det. 225 certified in the case management system checklist that Kelley’s fingerprints were submitted to the FBI.

“We attempted to assess the environment in which these special agents and supervisors worked when they failed to collect and submit the fingerprints and final disposition reports,” DoD IG investigators said. "We found several factors that created a challenging work environment. These factors included inexperienced special agents, individual personal issues at the time, leadership gaps, and a high operations tempo."

For example, the report said, five different special agents led AFOSI Det. 225 in the space of approximately four months; three of them were temporarily assigned for periods of roughly one to 10 weeks. In addition, four of the nine special agents assigned to Det. 225 were probationary agents with little to no experience in criminal investigations.

These difficulties were compounded by the high operations tempo of the office, according to the report.

Some agents told investigators that they received no formal training on submitting fingerprints, but the DoD IG found that to be untrue.

“Six of the AFOSI Detachment 225 Special Agents told us that they received no formal training on the submission of fingerprints,” DoD IG investigators said. “Yet, we found that the AFOSI did have fingerprint submission training at the Criminal Investigator Training Program and AFOSI Basic Special Investigators Course.”

Meanwhile, the training program for Air Force security forces airmen did not include instruction on the collection and submission of fingerprints and final disposition information to the FBI.

“In sum, we concluded that there was no valid reason for the [Air Force’s] failures to submit Kelley’s fingerprints and final disposition report to the FBI CJIS Division,” investigators said.

The Office of the Secretary of the Air Force highlighted some of the corrective actions the service has undertaken in the wake of their own review late last year.

In the near-term, AFOSI and Air Force security forces will disseminate updated guidance and conduct command-wide training on criminal history reporting guidelines and procedures, service leadership said in their statement. Commanders at all levels will also clearly articulate to airmen the need for total compliance and to assess local limitations, if any exist.

When all corrective actions are implemented, the Air Force Audit Agency will conduct a review to ensure effectiveness. That audit will be completed Jan. 11, 2019, the service said.

The Air Force is also in an ongoing process of sharing all lessons learned with the other services, service officials said in their statement.

The DoD IG’s methodology for this investigation included a multi-disciplinary team of special agents, investigative specialists and attorneys. The Pentagon offices subpoenaed Kelley’s criminal history and mental health records, and the team conducted 41 witness interviews, including interviews of Kelley’s ex-wife, his second wife and his father.

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.