Senior Master Sgt. Corey Fossbender has lost count of exactly how many times he’s deployed in his 26-year career in the Air Force.

Twenty-seven, maybe? Or 28, the AC-130U aerial gunner guessed.

Maybe more, though he’s certain he’s been to 19 different combat zones — several of them more than once.

“I couldn’t even tell you how many deployments I’ve had, but 19 combat deployments from Africa, Iraq, Afghanistan, and anywhere in between,” said Fossbender, who is the senior enlisted leader for the 4th Special Operations Squadron at Hurlburt Field, Florida.

He isn’t alone.

As the Air Force’s wars have shifted, the burden of deployments is increasingly falling on a specialized, in-demand cadre of crucial airmen — some of the most stressed in the service. Air Force leaders are increasingly worried that the pressure placed on these vital airmen is taking a toll on them and their families — and may even break the force.

“We’re burning out our people,” Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson said in a November news conference, where she discussed meeting an airman who had just returned from his 17th deployment. “At some point, families make a decision that they just can’t keep doing this at this pace.”

The Air Force is trying to take steps to better manage how its airmen deploy.

In December, it announced that airmen deploying on individual taskings will now be sent in teams of three or more — a new policy called Deployed Teaming.

This seeks to reduce the strain and pressure that comes when airmen deploy by themselves. Teammates will train together and “provide mutual support” when overseas.

The Air Force is also looking at its 365-day deployments to see if it’s sending the right number of people overseas for a full year, Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force Kaleth Wright said Nov. 27.

Across the entire Air Force, deployment rates appear largely unchanged between 2015 and 2016, at a median 1:5 deployment-to-dwell time rate, meaning most airmen stay at home five times as long as they spent deployed before going overseas again.

More airmen are deploying — 84,053 in 2016, up from 64,655 in 2015 — but the average deployment has shortened, from 131 days in 2015 to 98 in 2016.

The number of total days deployed dipped from 8.5 million to 8.3 million.

Warning signs

But a closer look at the data shows where the burden is falling — and where the warning signs are.

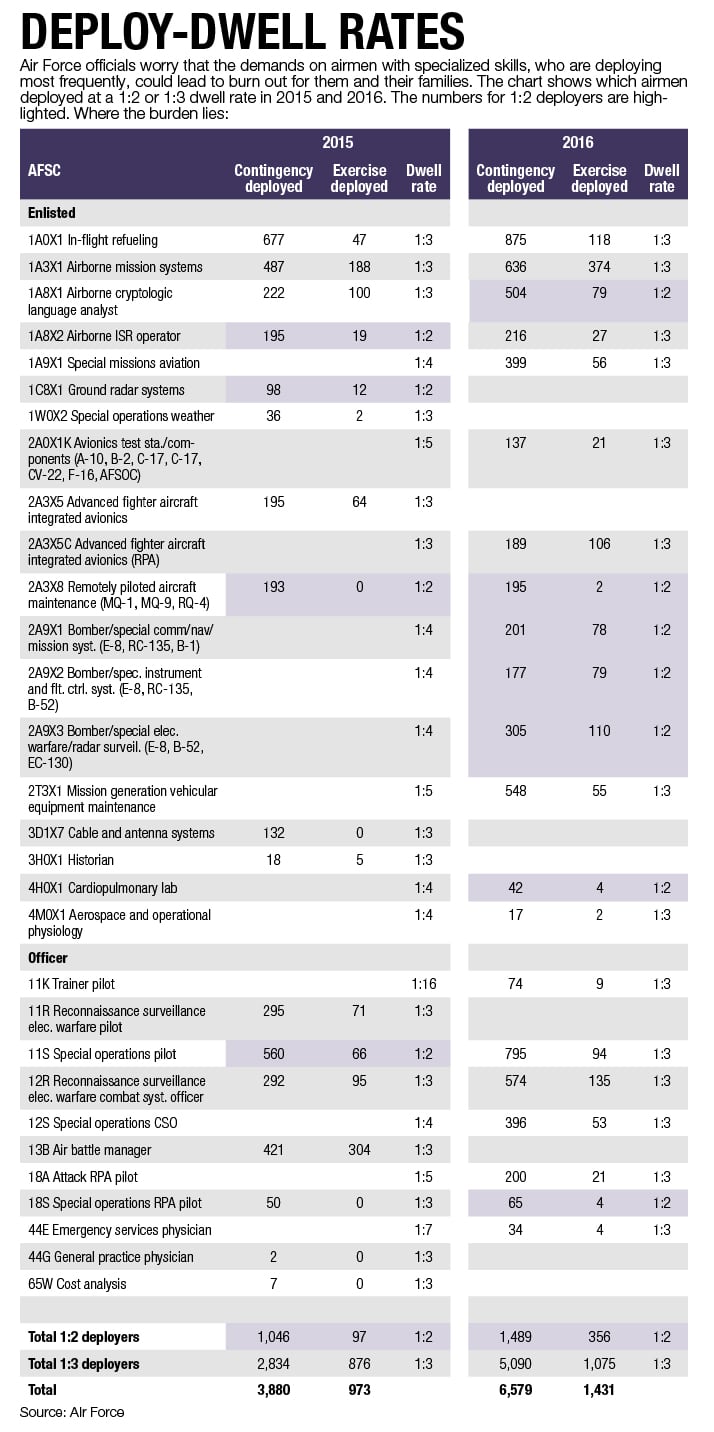

An Air Force Times analysis of deployment statistics shows that in fiscal 2015, 1,046 airmen who deployed for contingency operations overseas were in the four Air Force specialty codes that averaged a 1:2 deploy-dwell rate.

In fiscal 2016, 1,489 airmen deployed overseas in the seven career fields with 1:2 deploy-dwell ratios.

The change in jobs with 1:3 deploy-dwell rates was even more dramatic. In 2015, 2,834 airmen deployed in the 13 AFSCs with that rate. But in 2016, the number of airmen deploying in the 14 career fields with that rate dramatically increased, to at least 5,090.

Some of the career fields with the most demanding — and increasing — deployment rates are in missions that proved central to the air campaign against the Islamic State. For example, while 1A0X1 in-flight refuelers stayed at a 1:3 rate, the number of contingency-deployed airmen in that field increased from 677 to 875 between 2015 and 2016.

The deployment rate for 1A8X1 airborne crypto language analysts increased from 1:3 to 1:2 from 2015 to 2016, while the number of contingency-deployed airmen in that field more than doubled, from 222 to 504.

The number of contingency-deployed 2A9X1 airmen — who maintain and repair avionics systems for aircraft such as the B-1 and B-52 bombers and the E-8 JSTARS surveillance and command and control aircraft — nearly doubled from 109 in 2015 to 201 in 2016.

In 2015, the 2A9X1 career field had an average deploy-dwell rate of 1:4 overall.

But in 2016, the airmen in that job specializing in the B-1, E-8 and RC-135 were deploying at a 1:2 rate, and B-52 airmen were at a 1:3 rate.

“The handful of career fields that are [increasingly deploying at a 1:2 rate] are predominantly [intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance]-related, either maintenance or linguists, things like that,” said Don Cohen, chief of the force generation branch within the Air Force’s war planning and policy division. “As we go to more of a counterterrorism-type [mission], there’s a higher reliance on ISR.”

RELATED

The Air Force did not provide deploy-dwell statistics for 2017 to Air Force Times, instead providing a statistic called “perstempo,” or the operational tempo of Air Force personnel, which measures the percentage of time airmen in each AFSC spent away from home between Dec. 1, 2016, and Nov. 30, 2017.

Many of the AFSCs with the highest perstempo are the same that had the most frequent deployment ratios in previous years.

For example, 1A8X2 airborne ISR operators were deployed 14 percent of the time to support contingency operations, and were on TDY — such as for training and hospitalizations, but also including contingency operations deployments — a total of 25.9 percent.

Airmen in AFSCs beginning with 2A9 supporting the JSTARS, had exceptionally high rates, deploying to support contingency operations between 15 percent and 17.5 percent of the time. For context, across the entire Air Force, airmen spent about 4 percent of their time, on average, on contingency deployments.

‘Most-stressed career field’

But few career fields illustrate the challenges facing the Air Force and its airmen like 1A9X1 special missions aviators, or AC-130 gunners like Fossbender.

In Afghanistan and against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, the AC-130U Spooky gunship has become one of the Air Force’s most critical and feared weapons. It can loiter for hours above a battlefield, cutting down enemies with its fearsome 105mm Howitzer cannon, 40mm cannon, and 25mm Gatling gun.

As many as 289 1A9X1 special missions aviators — AC-130 gunners like Fossbender — deployed in 2015 at a 1:4 deploy-dwell rate. But in 2016, 399 aerial gunners deployed, at a 1:3 rate.

And in 2017, those gunners deployed overseas 8 percent of the time, and were on TDY 20 percent of the time.

In a November hearing on Capitol Hill, Lt. Gen. Mark Nowland, the Air Force’s deputy chief of staff for operations, called AC-130 gunners “the Air Force’s most-stressed career field,” and said there is an operator retention “crisis.”

“It’s always tough,” Chief Master Sgt. Gregory Smith, the command chief of Air Force Special Operations Command, said in a Nov. 29 interview.

“We’re in the middle of a pretty significant fight on multiple fronts. When you’ve been doing that for 16 years, there’s a toll that it takes on readiness and on the force.”

There are some recent signs of improvement, Smith and Fossbender said.

Over the past couple of years, Fossbender said, his airmen have typically deployed about four months at a time.

But this fall, they shifted to 90-day deployments — not including five or six days of travel to and from the combat zone — which helps, he said.

For a while, Fossbender said, his airmen in the 4th SOS were steadily deploying at a 1:1 rate. Some airmen were deploying even more frequently, he said, spending more time deployed overseas than at home. The secretary of defense had to issue rare waivers to allow those 4th SOS airmen to deploy at a sub-1:1 rate, AFSOC said.

But now, Fossbender’s airmen are spending a little more time stateside before deploying again, at a roughly 1:1.4 deploy-dwell rate — that is, after a 90-day deployment, they’re typically home for about 126 days. But they’re not yet at the 1:2 rate that is the Air Force’s goal.

Fossbender said his aerial gunners have “had a lot of ups and downs throughout the years” as far as deployment tempos go. Things got particularly tight over the last few years, when AC-130s had to return to Iraq to fight the Islamic State, while continuing to operate in Afghanistan.

“What really got us tight on our dwell was being in two combat zones,” Fossbender said. “That spread us real thin.”

And combatant commanders are increasingly eager to have gunships supporting their missions.

“Everybody wants a gunship,” Fossbender said. “Before, in the wars, a gunship was called in if needed. Now the missions don’t go without a gunship. We’re good at what we do.”

Some strategic decisions made in past years led to the strain Nowland described, Smith said.

In 2012, while the Air Force was out of Iraq and focusing primarily on Afghanistan, the service decided to recapitalize AFSOC airplanes, particularly the AC- and MC-130, he said. But in the middle of transitioning to the new 130 fleet — which occupied about 20 percent of those airmen — the ISIS war erupted.

Short-staffed, AFSOC airmen suddenly had to start supporting those new operations while maintaining operations in Afghanistan.

During those surge periods, Smith said, AFSOC was definitely below a 1:2 deploy-dwell rate — sometimes bordering on 1:1 for certain aircrew and battlefield airmen positions.

But, he said, things are getting better, especially as the war against ISIS is slowing down. AFSOC is now getting closer to 1:2, and hopes to eventually get back to 1:3. AC-130 airmen as a whole were at about 1:1.5 last year, though that pace has also eased some, he said.

Making changes

Smith said AFSOC has taken several steps lately to relieve deployment stress.

As the Air Force has moved to grow support staff in squadrons to free up pilots and air crew, AFSOC has pulled more AC-130 airmen out of staff jobs and put them back in aircraft, he said.

RELATED

AFSOC has also cut back on some professional military education opportunities to make as many AC-130 airmen available for deployments as possible.

They also have reviewed, Smith said, AC-130 airmen who have been medically deemed not mission-ready and non-deployable. Some of those airmen wanted to deploy but have been held back due to minor medical issues, he said.

Others with more serious medical issues have been moved to different jobs, such as at headquarters, to free up a slot for a new, deployable person.

Smith also said they’ve hired contract instructors to teach AC-130 airmen because they couldn’t afford to pull airmen off deployments to serve as instructors.

But with Congress incapable of passing a budget and the military forced to rely on continuing resolutions that freeze funding at last year’s levels, AFSOC can’t hire more civilian contractors that would allow it to better manage deployments.

“I have a lot of retired guys in the local area who have flown these airplanes for 25 years,” Smith said. “They’re phenomenal leaders and instructors and know what the requirements are downrange. They can fill that void very easily.

“But if I can’t start a new contract because of a CR, then I have to use guys that I would be deploying in an instructor role, which then increases the burden on the folks that are already deploying.”

Not just combat

It’s not only combat operations that strain airmen.

Col. Ethan Griffin, commander of the 436th Airlift Wing at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware, said that when hurricanes or other natural disasters strike — like Hurricanes Irma and Maria last year — his C-5 and C-17 airmen are pulled away to provide humanitarian relief.

One way or another, the 436th is going to have to respond to those disasters, in addition to their regular training requirements and operations to support missions in Afghanistan and elsewhere. But Griffin said they’re taking steps to make sure the pressure doesn’t fall too heavily on certain airmen, and doing what they can to relieve stress elsewhere.

The Air Force’s recent emphasis on empowering squadron commanders has helped better manage deployments, he said, since those commanders know their airmen and their personal situations best. For example, Griffin has empowered his squadron commanders to throw up a red flag when certain airmen are tasked for deployment.

If there’s a good reason why they shouldn’t go, the wing usually picks another airman or redirects the task. For example, one airman’s spouse was diagnosed with abdominal cancer, requiring multiple surgeries at a time when the family also had to care for a small child, according to an email from the 436th.

This airman was taken off the deployment schedule during the three-month period when the spouse was undergoing care. At the same time, the other spouses at the 436th helped provide meals and child care assistance for that family. The spouse is now recovering.

The 436th also postponed its Community Relations Tour this year — where leaders from Dover visit another base to learn more about how the Air Force operates — because it was scheduled during hurricane season, when operations tempos were high.

RELATED

‘Tough one to sell’

Fossbender, who has a wife and son, said the frequent deployments have been “a rollercoaster, ups and downs.”

Since regular Internet access — and technology like Skype and Facetime — have come to combat zones, it’s lessened the strain a little bit.

But his wife has become “less of a fan” of his frequent deployments, which means they have to talk about it and work through those conflicts.

“What we do is high risk,” Fossbender said. “Just having your spouse in harm’s way … it’s a tough one to sell.”

The toughest times are when he can’t talk to his wife and family for a few days or a week, which causes concerns.

“It’s trying,” Fossbender said. “It’s tough. Sometimes that separation makes a little bit more fondness, because you’re not taking for granted all the things that you did when you’re at home. Knock on wood, my wife and I and family have managed through it.”

Staff Sgt. Gregory Hosko, another aerial gunner at the 4th SOS, doesn’t have a wife or kids and said he enjoys frequent deployments.

“I would rather take the strain than put it onto somebody else that’s married and has kids,” Hosko said. “If I can step in and say, ‘I’ll sign that dwell time waiver, let this guy hang back for Christmas or Thanksgiving, and let him enjoy time with his family,’ … I’m totally fine with doing that.”

But Hosko has sacrificed time with his family as well. He was once called up for a no-notice deployment and had to be on a plane within four hours. As a result, he missed his brother’s wedding, where he was supposed to be best man.

“That kind of sucked, but it was just one in the eight years I’ve been in,” Hosko said.

Despite the pressure, Fossbender said his airmen are usually “champing at the bit after a couple of months to get out there and kill more bad guys.”

RELATED

But even so, Hosko said, it’s not easy.

“Knowing that any point in time, you have to leave, you can’t tell your parents where you’re going, when you’re coming back, it’s like the dark cloud that hangs over you,” he said.

Even when airmen like Fossbender and Hosko are home, they’re still tied down. Not only do they often have to train when they’re stateside, they’re also committed to supporting the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff if anything else flares up around the globe.

“Even when we’re not deployed, we’re still on the hook,” Fossbender said.

His unit is tight, he said, and the families “circle the wagons” to help each other out when airmen are deployed.

This helps ease the strain of frequent deployments a bit — but not entirely.

When asked if he’s seen his fellow airmen leave due to deployment pressures, Fossbender said, “Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. It’s a tough one.”

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.