A single sentence in the Journals of the Continental Congress defines our flag’s origins: “Resolved, That the flag of the United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white: that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.”

We don’t know which member or committee introduced the Flag Resolution of June 14, 1777, and we don’t know if the measure was debated or who voted for or against it. The Congress adopted the resolution without comment, not bothering to specify the flag’s shape, proportions or the size of the canton or field of stripes. Nor did the resolution say anything about the shape of the stars nor their pattern in the constellation.

The Betsy Ross myth notwithstanding, we really don’t know who designed the American flag, why it’s red, white, and blue, or why it features stars and stripes.

From today’s perspective, America’s first flag seems an afterthought, far from the archetypal symbol it would become in the 19th century, a period of territorial expansion and internal strife. It would be a stretch, in fact, to say that in 1777 Americans even recognized the Stars and Stripes as the national emblem or symbol. “The American flag as a sovereign flag did not occur until 1782,” says early American flag authority Henry Moeller. “In the 1777 period, the flag was not a device that was used by the average citizen. It was used for communication,” Moeller contends, primarily by the military, and mainly on Navy ships. Most historians of the period concur.

From the Revolution to the present conflict in Iraq, use of the flag has progressed from primarily a naval emblem rarely flown by patriotic citizens to a widely revered national symbol. And the most significant steps in the evolution of Americans’ attitude toward their flag have been taken in wartime.

And so, despite the impressions left by latter-day paintings such as German-born Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s apocryphal George Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851), the Revolutionary War was not fought under the Stars and Stripes.

The Continental Army officially engaged British troops under what was known as the Continental Colors or the Grand Union flag, the banner General Washington flew for the first time at the army’s birth on January 1, 1776. That flag had the familiar 13 red and white stripes, but its canton contained the Union Jack.

Washington quickly realized that it wasn’t the best idea to fly it while fighting the British because enemy officers saw it as a sign of surrender. So the Continental Army fought the British primarily under unit and militia flags, some of which contained 13 stars and 13 stripes. Among them were the well-known Bennington Flag with its seven white and six red horizontal stripes and a canton containing the number “76,” above which 11 stars were arrayed in a semicircle with two additional stars above.

The most famous single American flag, the tattered Star-Spangled Banner now in the possession of the Smithsonian Institution, is a product of the nation’s second conflict with Great Britain, the War of 1812. That flag, measuring an impressive 42 feet wide by 30 feet high, was sewn by Mary Pickersgill in Baltimore for U.S. Army Maj. George Armistead, the commander of Fort McHenry in that city’s harbor. The story of Francis Scott Key witnessing British ships bombard Fort McHenry on Sept. 12-14, 1814, is famous. Less well known is what Key, a Washington lawyer and amateur poet, was doing in the harbor when the bombs were bursting in air.

Key and U.S. Army Col. John S. Skinner were in Baltimore negotiating the release of an American doctor who had been taken by the British in the Battle of Bladensburg in August. Key did persuade the British to release Dr. William Beanes, but the Americans were not permitted to return to Washington until after the British attack on Baltimore. And so Key, Skinner, and Beanes spent four days on a sloop in the harbor, observing the fighting, including the relentless barrage during the stormy night of Sept. 13.

As the British fleet sailed away, Key jotted down his emotions in long rhyming lines on the back of a letter he was carrying in his pocket and completed the four verses a day or so later. Baltimore printer Benjamin Edes published Key’s poem, “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” on handbills and broadsheets and distributed them throughout the city. The Baltimore Patriot and Evening Advertiser published the poem on Sept. 20, and the accompanying article indicated that it was to be sung to the tune of “Anacreon in Heaven,” an English pub song well known to Americans.

Although the American naval ships in Baltimore Harbor flew the banner prominently, the U.S. Army didn’t get around to adopting the Stars and Stripes as its official garrison flag until 1834. The directive came in the form of a General Regulation that applied only to artillery troops. Infantry regiments received that order seven years later, in 1841. And so the first war officially fought under the Stars and Stripes was the Mexican War of 1846-48.

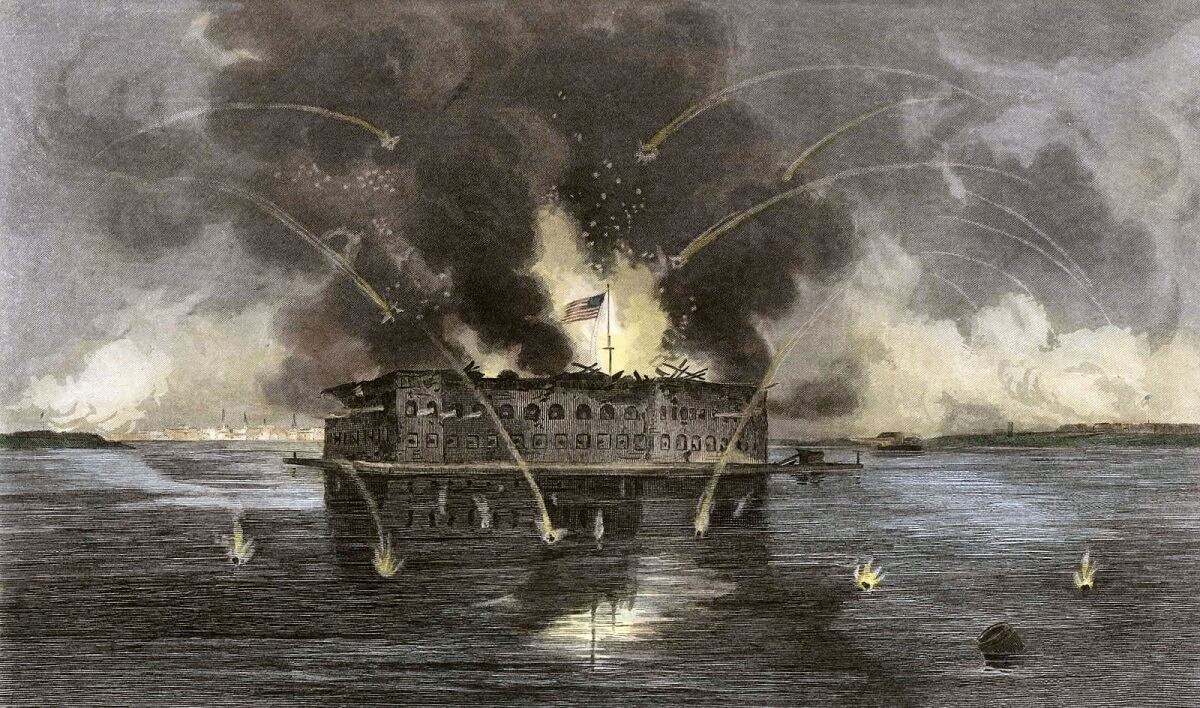

Nearly 60 years after Key penned his battle account in Baltimore and soon after the first firing on Fort Sumter in April 1861, “The Star-Spangled Banner” gained popularity in the North. Use of the song in the first year of the Civil War, in fact, marked the first time that the nation significantly embraced the flag as a symbol of American patriotism. Northerners spontaneously unfurled American flags in front of their houses, places of business, churches, schools, and colleges as soon as they learned of the fall of Fort Sumter. “Every city, town, and village suddenly blossomed with banners,” one observer wrote. In the decades to follow the song grew in popularity nationwide.

The events in Charleston’s harbor “created great enthusiasm throughout the loyal States, for the flag had come to have a new and strange significance,” Admiral George Henry Preble wrote in his pioneering 1871 book “History and Origin of the American Flag.”

“The heart of the nation swelled to avenge the insult cast by traitors on its glorious flag. It is said that even laborers wept in the streets for the degradation of their country. One cry was raised, drowning all other voices—‘War! War to restore the Union! War to avenge the flag!’”

Northern partisans framed the fight against the Confederacy as a fight for the American flag. Newspapers and magazines in the North ran red-hot flag-oriented editorials. “The Battle Cry of Freedom” with its stirring words “we’ll rally round the flag, boys” was a wildly popular song.

The first Union martyr, Col. Elmer Ellsworth, was shot dead by an innkeeper in Alexandria, Va., in May 1861 after Ellsworth tore down a Confederate flag at the inn. “Remember Ellsworth” became a Union rallying cry. Printed on broadsides, postal envelopes and letterheads, it was always accompanied with an image of the red, white, and blue.

Meanwhile, for the Confederate Congress, almost the first order of business was coming up with a national flag. Debate centered on how closely the new flag should resemble the Stars and Stripes. The Stars and Bars, with its red, white and blue colors and its wide stripes and stars in a canton, did borrow heavily from the American flag. The Confederate Battle Flag, perhaps more recognizable today, came into being after First Manassas, when Rebel generals complained they often couldn’t distinguish the American and Confederate flags on the smoke-filled field of battle.

The so-called “cult of the flag” that began in the North in April 1861 spread nationwide in the decades following the Civil War. The most prominent proponent of the popularizing of the flag was the nation’s first powerful veterans’ service organization, the Grand Army of the Republic, which formed shortly after the war and was made up of Union veterans. The GAR, from its beginnings, promoted patriotism and the use of the flag. Finally, in 1931, after a long lobbying effort by patriotic and veterans groups, notably the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, Congress elevated Key’s 117-year-old lyrics set to a British drinking song to national-anthem status.

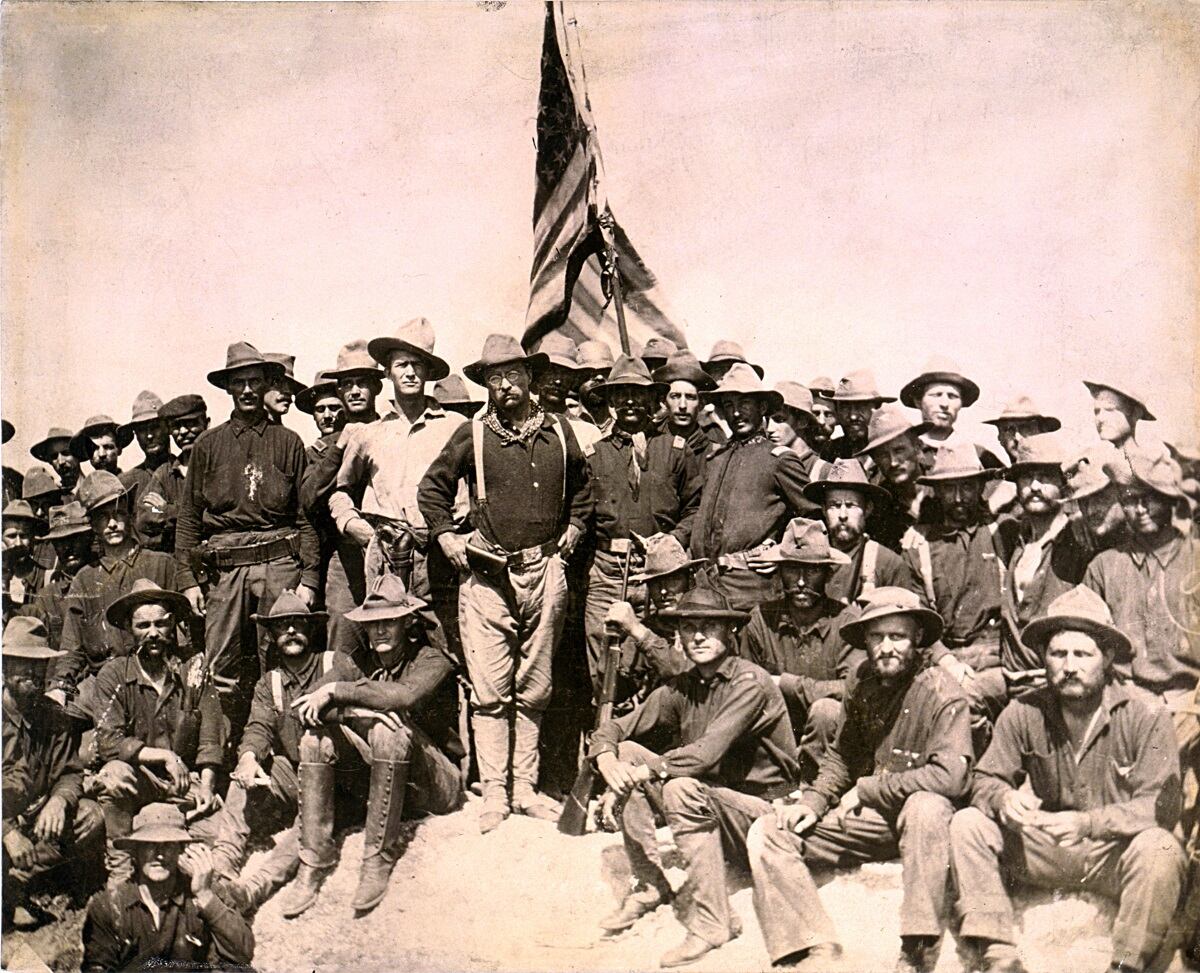

The Spanish-American War of 1898 was the first foreign conflict fought by the entire nation under the Stars and Stripes since the Mexican War had ended 50 years earlier. Americans from states that opposed each other under the Confederate and Union banners united under the 45-star American standard to fight in Cuba and the Philippines. Former Confederate Gen. John Brown Gordon, expressing a common sentiment as the war began, pledged that Southerners would fight the Spanish “wrapped in the folds of the American flag.”

The “greatest good” of the Spanish-American War, New York Gov. Theodore Roosevelt said in August 1899, “was that beneath the same banner marched the sons of the blue and the gray. The nation is now united in deed as well as in name. After being the son of a man who wore the blue, the next best thing is to be a son of a man who wore the gray. We are now all Americans, proud of our forefathers and their bravery on both sides.”

Indeed, Americans nationwide went on a flag-flying spree. “The demand for bunting within the last ten days is in excess of the supply,” the Wall Street Journal reported on May 2, 1898. “The demand is such that orders have been taken for delivery from three to four months ahead.” Not surprisingly, prices for bunting and flags had risen precipitously, according to the Journal.

America’s entry into World War I hastened an outburst of flag-waving that resembled the North’s at the start of the Civil War. On April 6, 1917, only hours after the United States declared war on Germany, flags were displayed from public and private buildings all across America. “Though [New York City] has been besprinkled with flags in the last weeks, a veritable flood of bunting broke forth yesterday,” The New York Times reported on April 7.

In Washington, D.C., in response to a nationwide public outcry, American flags were flown around the clock over the east and west fronts of the Capitol. Flag-waving patriotic pageants, with such names as “Building of the Flag, or Liberty Triumphant” and “A Pageant of the Stars and Stripes,” were held throughout the nation. In 1916, during the war buildup, President Woodrow Wilson had first proclaimed June 14, the 139th anniversary of the 1777 Flag Resolution, as Flag Day.

With entry into the war, the American flag became popular in Canada, Britain, France, Belgium and elsewhere in Western Europe outside of Germany. For the first time in tradition-bound Great Britain, another nation’s flag—the Stars and Stripes—flew with the Union Jack outside Parliament. In Paris the U.S. flag was displayed at the French National Assembly at the Palais Bourbon next to the French tricolor, and America’s symbol decorated Parisian boulevards and the streets of other French cities.

Several states strengthened the language of their flag-protection laws and increased the penalties for disobedience during World War I. The measures, passed in the late 1880s, originally were intended to cut down on commercial uses of the flag. Early in 1917, Congress made the manufacturing, selling, or advertising of items decorated with American flags a misdemeanor within the District of Columbia, punishable by a $100 fine or 30 days in jail.

Not long after the United States entered the war, the U.S. Department of Justice issued a directive, ordering that Germans and other aliens who were discovered “abusing or desecrating” the American flag “in any way” would be subject to “summary arrest and confinement” as a “danger to the public peace or safety” for the duration of the war. In 1918 Congress passed and President Woodrow Wilson signed into law an amendment to the June 1917 Espionage Act, popularly known as the Sedition Act. The new measure, among other things, made it illegal to “willfully utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” about the Constitution, the government or the America flag.

On the day the United States declared war on Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Americans everywhere once again rallied around the flag. “As if by magic, Fifth Avenue and other [New York] thoroughfares showed a spontaneous display of American flags” The New York Times reported on December 8, 1941. Filmed performances of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” shown before movie features, soon became standard at theaters across the country.

World War II also gave us the iconic image of the flag-raising at Iwo Jima, the scene of one of the bloodiest battles of that or any other war. The name of the strategically significant Pacific island name will forever be associated in American history with the American flag and the actions of five Marines and one sailor on February 23, 1945. That’s when Marines Ira Hayes, Franklin Sousley, Harlon Block, Michael Strank and Rene Gagnon and Navy Pharmacist’s Mate John Bradley raised a large American flag attached to a drainage pipe left behind by the Japanese atop Mount Suribachi.

Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal was on assignment with the military’s still picture pool, and caught them in the act. “People ask, ‘Was the picture posed?’” Rosenthal said in a 1950 interview. “No, it wasn’t. I went into the beach on a [landing craft]. I heard the boys were going to plant the flag, so when we landed I dashed right up the hill. I had a couple of minutes to get set while they were getting the flag ready, but they didn’t pose. I just caught them in a candid shot. The light and the wind were with me. It was a million-to-one lucky break.”

The photo appeared in hundreds of newspapers on February 25 and immediately triggered a patriotic sensation. Responding to demands from readers, newspapers across the nation published special editions that primarily contained the stirring photo. The single most recognized image of the war, it captured a Pulitzer Prize and other top photojournalism awards for Rosenthal, and became one of the 20th century’s most reproduced images.

Of the six men in the photograph, only Bradley, Hayes and Gagnon survived the fighting on Iwo Jima. President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the three to travel to Washington, where they were treated as heroes and made the centerpiece of the Seventh War Bond Drive. The Treasury Department commissioned a color poster of Rosenthal’s photo, and 3.5 million copies were distributed around the nation. Stores, theaters, banks, factories and railroad stations displayed them, and there was also a billboard version.

Austrian-born sculptor Felix de Weldon, serving as a U.S. Navy aviation artist in Virginia, was one of the first to see the photo. De Weldon later said that he was so taken by the image that, on his own, he worked virtually nonstop for three days to create a 3-foot-high model made from a mixture of floor wax and sealing wax because modeling clay was unavailable. De Weldon’s makeshift model so impressed Defense Department officials that they commissioned him to create a version in plaster, which the government sent on the nationwide war-bond drive. The three survivors posed for the plaster version, and de Weldon employed Rosenthal’s photo and other images for the three Marines who had died.

After the war Congress, prodded by lobbying from military and government officials, passed a joint resolution commissioning de Weldon to create an outdoor memorial to the Marine Corps with a version of his statue as the centerpiece. It took more than nine years for de Weldon and his team to complete the 100-ton, 48-foot-high bronze set piece. Placed on a hillside near Arlington National Cemetery, the Marine Corps War Memorial was dedicated by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on November 10, 1954, the Marine Corps’ 179th anniversary. The memorial, maintained by the National Park Service, is dedicated to all Marines who have lost their lives in action since 1775. In 1961 President John F. Kennedy signed a proclamation giving sanction to flying the American flag 24 hours a day from a 100-foot-high flagpole at the memorial.

Wedged in the middle of the 20th century between World War II and Vietnam, the 1950-1953 Korean War is sometimes called America’s forgotten war. True to that sobriquet, no iconic event involving the American flag took place in Korea. During the long and controversial Vietnam War, however, the flag took on new meaning as a symbol for that divisive conflict’s detractors as well as its supporters. By the end of the 1960s, the United States found itself engaged in what political scientist Robert Justin Goldstein called “a cultural war using the flag as a primary symbol.”

In a country polarized into war hawks and peace doves, the hawks held the flag as the primary emblem of their support for the war goals, their anticommunism stance and their disdain for those who spoke out against the war. Barry Goldwater, the conservative Republican senator from Arizona who ran against President Lyndon Johnson in 1964, for example, began his campaign rallies with a recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance. And he received thunderous applause from campaign audiences when he pledged — as he did at a rally in Los Angeles in March 1964 — that he would not tolerate the Stars and Stripes being “torn down, spat upon and burned around the world.”

Doves employed the flag as well, frequently showing it upside down as a sign of distress; they created posters with the stars arrayed in the peace sign and other forms of protest; they wore flag shirts and bandannas; or they simply flew the Betsy Ross flag or the 50-star flag. The most radical elements of the antiwar movement defiantly displayed the Viet Cong flag, and some burned the Stars and Stripes to protest the American war in Vietnam, which led to passage of the first national flag desecration law in 1968.

In marked contrast, most Americans united behind the Stars and Stripes at the outset of the 1991 Persian Gulf War. And 10 years later, within days of the September 11 attacks, millions of Americans proudly and defiantly unfurled American flags. Again, when the United States began military operations against Iraq in March 2003, the American people reacted with impressive displays of the American flag in support of the troops.

And then, for perhaps the first time since the military began flying the Stars and Stripes in the War of 1812, American troops — whose uniforms contain an American flag patch on the right sleeve — were ordered not to fly the Stars and Stripes in Iraq. The reason was to avoid the impression that the Americans were leading an invasion. The directive, though, was not strictly followed.

Some American troops, including Cpl. Edward Chin of the Marine Corps’ 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines, defiantly carried the Stars and Stripes with them into Iraq. On April 2, 2003, Chin and another Marine climbed to the top of a large statue of Saddam Hussein in Firdos Square in Baghdad as a crowd tried to dismantle it.

Chin covered the statue’s face with an American flag just before the statue came down. The flag remained displayed on it for only a few minutes before an Iraqi flag replaced it, but Abu Dhabi television broadcast the image live.

Two weeks later, when a group of Marines unfurled an American flag as they took over a regional governor’s office in Mosul, Iraqis began a violent street protest over the flying of the Stars and Stripes. In the ensuing firefight, at least seven Iraqis were killed. “You must respect the flag,” an Iraqi said. “They say to us they want to leave our country soon. How can we believe them if they put up the American flag?”

Officially or not, Americans have put up their flag in wars since the Revolution. Although patriots throughout the world are attached to their national emblems, Americans seem to have an especially personal relationship with the Stars and Stripes. Wartime has invariably intensified those feelings.

Historian and journalist Marc Leepson is the author of six books, including “Flag: An American Biography” (Thomas Dunne Books at St. Martin’s Press, 2005), a history of the American flag from the beginnings to today, upon which this article is based. He served with the U.S. Army in Vietnam in 1967-68.

Originally published in the March 2007 issue of Military History Magazine, a sister publication.